Thoughts on "Beneficial Effects of Linoleic Acid on Cardiometabolic Health: An Update"

tl;dr: It's quite remarkable what you have to do to find these 'beneficial' effects.

So no sooner do I write this post and publish it on September 3:

A Conspiracy to Protect Linoleic Acid?

I have been noticing for years a peculiar phenomenon: papers that ought to be discussing linoleic acid’s role in disease oddly ignore it.

Than this paper is released on September 12:

“Beneficial Effects of Linoleic Acid on Cardiometabolic Health: An Update” (Jackson, 2024)

Toward the end of my ‘conspiracy’ post I had the following section:

And then there’s the American Heart Association.

They demonstrated in the 1960s and 1970s that linoleic acid causes heart disease (Ramsden, 2016; Newport, 2024), despite the their recommendation that it be consumed to reduce heart disease (Page, 1961).

Even after it was demonstrated that linoleic acid played a clear role in heart disease (Brown, 1990; Steinberg, 1989), and that reducing it might benefit heart disease (de Lorgeril, 1994); they continued to ignore that role (Kris-Etherton, 2001; Sacks, 2017).

The last two papers mentioned, (Kris-Etherton, 2001; Sacks, 2017), were both official issuances of the AHA. Penny M. Kris-Etherton was first author of the 2001 paper and a co-author of the 2017 paper. She’s a co-author of this paper, too

But, before we go through the other authors, let’s take a look at the paper. (All quotes in bold are from (Jackson, 2024), unless otherwise noted.)

A Brief History of Seed Oils

“High LA [linoleic acid] seed oils are a novelty in the human diet, being introduced in the 1800s with the surplus of cottonseeds from the US cotton industry.”

This is not quite correct, they were originally introduced some 5,000 years ago (Bedigian, 1986), but this is good enough for the current discussion.

“Cottonseed oil is microbiologically stable and was originally produced for industrial applications such as lubricants.”

This is a popular meme on the internet, but is not actually true. “Its lubricating properties are poor, as it comes in between the drying and the non-drying oil.” It was used briefly as a lamp oil, a replacement for whale oil, but this use was extinguished by much-cheaper kerosene. “The garbage of 1800 became the fertilizer of 1870, the cattle food of 1880, and is now made to yield table food and useful articles of industrial pursuits.” (Grimshaw, 1889)

And Then Downhill…

It’s never a good sign in a research paper when the first few facts claimed are erroneous. But we’ve got miles to go…

“In 1957, the American Heart Association (AHA) issued a report that summarized the evidence about the relationship between diet and atherosclerosis and concluded that diet likely played an important role, and that the balance between saturated and unsaturated fat may also be important [7].”

What (Page, 1957) said, in fact, was that (in discussing unsaturated fats and causation of CVD):

“It is important to keep in mind that the "test conditions" (variously, formula diets, tube feeding, grossly distorted diets, hospitalized patients, medical students, poor Bantus) do not necessarily bear directly on the possible effects of addition of reasonable amounts of unsaturated fat to a North American "meat and potatoes" diet, and, at present, cannot be extrapolated to the normal diets of large groups of people free of cardiovascular disease….

“Thus, the evidence at present does not convey any specific implications for drastic dietary changes, specifically in the quantity or type of fat in the diet of the general population, on the premise that such changes will definitely lessen the incidence of coronary or cerebral artery disease.”

Jackson et al. continue:

In 1961, an ad hoc AHA committee updated the earlier report and concluded that diet should be modified by decreasing total fat, saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and cholesterol and increasing PUFAs [8].

This is correct, but it should be noted that (Page, 1961) observed that there was no dramatic change in the evidence base.

“It must be emphasized that there is as yet no final proof that heart attacks or strokes will be prevented by such measures.”

Or, as put more concisely in (Woodhill, 1978) about their study (The Sydney Diet-Heart Study, SDHS), which commenced in 1964:

“The dietary hypothesis had never been submitted to a field test.”

No human randomly-controlled trial (RCT) had shown that this change would be safe and effective. Jackson et al. don’t mention that. We’ll see why later.

Dr. Irvine Page, it should be noted, was president of the AHA from 1956 to 1957.

“A Robust Evidence Base…”

“Here, we outline the recent evidence supporting the hypothesis that higher intakes of LA are associated with improvements in relevant biomarkers and with lower risk for developing cardiometabolic diseases, and we address some of the most common concerns about higher LA intakes and levels.” (Jackson, 2024)

There are two problems here: “recent” and “associated”.

Neither Jackson nor their sources make clear that when the AHA made the recommendation described above, we had already seen a massive increase in the consumption of seed oils. (Jackson, 2024) states, “There is no question that LA has increased in the US food supply over the past century [1]…” citing (Blasbalg, 2011) from which comes this graph of LA consumption:

The two red bars (my notation) indicate the two AHA papers. We had already increased our consumption of polyunsaturated fats, and yet, as a source cited by (Page, 1957) made clear:

“The overall incidence of acute myocardial infarction among the Barnes autopsies was 29 times as high in the decade 1945 to 1954 as it was in the decade 1910 to 1919… The rise occurred in all age-groups of both sexes and was not simply a result of an ageing population.” (Thomas, 1957)

Neither Jackson nor the AHA explain why the increase in LA accompanied an increase in CVD, nor why a further increase might reverse the increase in CVD.

In medicine, the most robust evidence is that from a RCT, and if you have a bunch of them, you can tie them together in a meta-analysis. Meta-analysis has its issues (as do RCTs) as we shall see, but that’s about as close as you’re going to get to ‘truth’ in this realm.

Below experiments (a RCT is an experiment) in this hierarchy, we have ‘risk factors’ and epidemiology. For instance, if you consider cholesterol in blood to be a risk factor for heart attack (myocardial infarction), and you do an RCT that shows that a change in diet lowers cholesterol, you have not shown that you are accomplishing your goal.

“Is there compelling evidence that, if we treat the hypercholesterolemia by dietary means, we are doing anything to lessen the chances of myocardial infarction?” (Page, 1957)

What if, say, lowering cholesterol is accompanied by higher mortality? Obviously then, lowered cholesterol would not be an appropriate risk factor! And any study that reported lowering cholesterol as a positive finding would be misleading, at best.

What we care about is avoiding dying from the heart attack All these risk factors and associations are supposed to enlighten us on how to avoid that fate. Epidemiology, the “associations”, is so fraught with problems, that if we have some decent experimental evidence, it’s probably not worth delving into those issues.

If, "Nutritional epidemiology is a scandal, it should just go to the waste bin." as John Ioannids said (Crowe, 2018), is going a bit to far, nutritional epidemiology and CVD is the area that might make one consider it.

The section titled “Randomized controlled trials of LA and cardiovascular disease” contains a reference to an old (2010) meta-analysis of RCTs as its opening reference (Mozaffarian, 2010).

“A 2011 [sic] meta-analysis of seven RCTs in which PUFA-rich vegetable oils replaced SFAs and the effects on coronary heart disease were examined found a 19% overall reduction in risk [55].”

Now 2010 (not 2011) isn’t really old, but it’s odd to lead with this when a number of subsequent meta-analyses of RCTs have been done (Hamley, 2017; ; Harcombe, 2016; Hooper, 2015, 2018, 2020; Ramsden, 2010; 2013; 2016), especially given that (Mozaffarian, 2010) had severe enough defects that (Hamley, 2017; Hooper, 2010; 2015 and Ramsden, 2010) directly addressed and refuted it.

“However, we included two appropriate n-6 specific PUFA RCT with unfavourable outcomes(37,38) that were not analysed by Mozaffarian et al.(7).” (Ramsden, 2010)

“Mozaffarian et al. [19] was the only meta-analysis to find a significant reduction in risk for CHD mortality, which is mostly due to their inclusion of FMHS and their exclusion of SDHS.” (Hamley, 2017)

As Hooper notes, the FMHS (Finnish Mental Health Study) was not a RCT, it was not randomized (Hooper, 2010, 2018), so it should not have been included. But it favored their hypothesis, and SDHS which disfavors their hypothesis is excluded for the reason given below.

My notes on (Mozaffarian, 2010) include:

Bogus exclusions (cherry-picking):

Rose 1965—Rose Corn Oil: “Multiple interventions”. Intervention was reduction of SFA and increase polyunsaturated fat (n-6 via corn oil) or olive oil in two separate wings. Negative result.

vs. Burr 1989—DART included: 3 separate wings, one was reduction of saturated fat an increase of unspecified polyunsaturated fat. Same intervention as Rose.

Positive result.Woodhill 1978—Sydney Diet Heart: “Non-CHD endpoint” is reason given for exclusion. Title of study is “Low fat, low cholesterol diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease.” CHD was the primary endpoint.

Negative resultDe Lorgeril 1994—Lyon Diet Heart: “Multiple interventions” excluded. This did have multiple interventions, one of which was a REDUCTION in n-6 PUFA, along with other fats; increase in n-3 PUFA (large decline in CVD with REDUCTION in PUFA).

Negative result

vs. Watts 1992—STARS included: “Multiple interventions” included reduction in total fat and SFA, increase in n-6 and n-3 PUFA, increase in fiber. n-6 and n-3 not measured or defined.

Positive resultPoor quality of included/excluded decisions also noted by Hooper 2010 and Hamley 2017

So Mozaffarian et al. used whichever rationale was appropriate to exclude negative results and include positive ones.

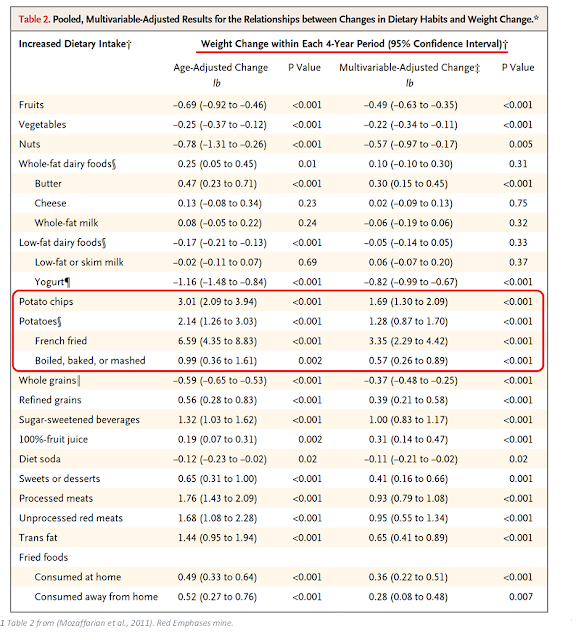

I reviewed another of his studies (Mozaffarian, 2011) from the following year in this post:

In that study he and his co-authors misrepresented the result of their study to hide the fact that added seed oils increased the obesogenic potential of potatoes dramatically. I also discussed this paper in the conspiracy post above.

I’d say his credibility is a bit shaky, but he’s said so himself, regarding another of his papers: “‘The conclusions weren’t exactly accurately written,’ acknowledged Dariush Mozaffarian, the dean of policy at Tufts’ nutrition school and a coauthor of the paper” (Johns, 2023). Just as with the potato paper above.

All the rest of the meta-analyses find, at best, “little or no difference to all-cause mortality” (Hooper, 2018) to harm. Certainly no benefit.

In fact, Jackson attempts to slip one past us. “…a 19% overall reduction in risk…” is not risk of death from all causes, but only risk of death from cardiovascular disease. So even Mozaffarian fails to find a benefit. Would you really prefer a long painful death from cancer instead of from a quick heart attack?

So why do Jackson et al. include only this meta-analysis? “This finding is generally consistent with epidemiological observations.”

For the epidemiological observations they refer us to FORCE, the Fatty Acids and Outcomes Research Consortium, an enterprise of Tufts University.

“The studies discussed below are from a group of nutrition research centers called the Fatty Acids and Outcomes Research Consortium (FORCE) [23].”

Who runs FORCE?

An epidemiological result doesn’t really matter if it can’t be confirmed experimentally. That’s what RCTs are for: to confirm hypotheses from observations and epidemiology.

I discussed in this post a famous example of epidemiology that didn’t get confirmed by RCT:

This concerned vitamin A and lung cancer. Epidemiology led scientists like Willett to think that beta-carotene would improve outcomes. Supplementation led to higher deaths in an RCT with Willett as a collaborator—you won’t easily find any mention of the failure on that page!

Willett is also a member of FORCE.

If you have RCT evidence that something happens, subsequent epidemiology doesn’t void or supersede that result. Doing another survey showing that beta-carotene ‘associates’ with benefit in lung cancer doesn’t erase the two trials showing that it is harmful.

Science doesn’t work like that.

Now, Jackson et al. do mention another meta-analysis. They don’t tell you that it’s a meta-analysis, however:

“However, Ramsden et al. in a series of papers raised questions about the validity and interpretation of several of these studies, suggesting that in fact, higher LA intakes might at best be neutral, and possibly even adverse [56, 57].”

While no mention is made of the critiques of (Mozaffarian, 2010), or the fact that it has not been reproduced by any of the subsequent meta-analyses, Jackson et al. present ample ‘evidence’ that Ramsden’s work isn’t worthy of consideration:

In response to these reports, a variety of rebuttals were published that challenged the Ramsden conclusions and re-affirmed the beneficial effects of PUFAs substituting for SFAs [58–60].

And thus you shouldn’t be worried about this paper.

A detailed review of this particular controversy is, however, beyond the scope of the present paper.

Misdirection

This is a neat attempt at misdirection. If these authors wanted to present a comprehensive review of the subject, this would be the core of the discussion. It’s such an attempt at misdirection, that they don’t even refer to the meta-analysis (Ramsden, 2016)—although their reference 58 (Skeaff, 2016) purports to be a refutation. They do refer to (Ramsden 2013), however.

Why is this so critical?

We’ve already discussed the two papers from the AHA which Jackson et al. mention as being key to the idea that consuming seed oils is beneficial for cardiovascular disease (Page, 1957, 1961), and noted the lack of RCT evidence to support this recommendation.

Well the AHA didn’t leave it at that. (Page, 1961) mention that a trial was underway in 1961 (The Anti-Coronary Club, results reported in (Christakis, 1966)), but the AHA had also decided to start their own trial, the National Diet-Heart Study (NDHS).

“In 1960, with the support of the National Heart Institute of the US Public Health Service, an Executive Committee on Diet and Heart Disease was established under the chairmanship of Dr. Irvine H. Page of Cleveland. This committee included leading medical, nutritional, and epidemiological scientists, as well as liaison representatives of the American Heart Association, the American Medical Association, the National Heart Institute, and the Nutrition Foundation.” (Baker, 1963)

The most controlled portion of this experiment was led by Dr. Ivan Frantz:

“The design of the feasibility study involves the recruitment of approximately 1,500 healthy, male volunteers. (Dr. Frantz's study will be conducted in a controlled, hospital environment; the other studies involve men living at home. )”

This was a massive enterprise. The U.S. Census was involved, as were many life insurance companies.

“For the other test diets, at least thirty food manufacturers were recruited to create special foods which included oil-filled sausages and patties, imitation eggs, imitation ice cream, imitation cheese loaves, coffee creamers with hydrogenated oils, margarines, cakes, pastries, and oil emulsions to replace natural food items, such as dairy fat.” (Newport, 2024)

Dr. Frantz’ portion of the study became the Minnesota Coronary Experiment (MCE). It was a continuation of the most controlled portion of the NDHS:

“The MCE experimental serum cholesterol lowering diet was derived from the “BC” diet of the institutional arm of the National Diet-Heart Feasibility Study at Faribault Hospital.” (Ramdsen, 2016)

So if you’re going to cite the AHA’s advice on how to eat to prevent heart disease, shouldn’t you include the result of their RCT, and discuss it forthrightly?

What Did the American Heart Association & Co. Find?

Despite all the resources, the NDHS was a failure.

“The results from the three stages of the NDHS suggest that the typical American diet and the created diets, all of which contained significant amounts of trans-fats, produced comparable cardiovascular outcomes….

“The NDHS… did not prove that replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat reduces deaths from CHD.” (Newport, 2024)

The MCE was also a failure.

Not only did the intervention group (eating more polyunsaturated fats) have higher mortality than the control group (Frantz, 1989), but the increase in mortality was in proportion to the cholesterol-lowering effect of the diet.

“Paradoxically, MCE participants who had greater reduction in serum cholesterol had a higher rather than a lower risk of death.” (Ramsden, 2016)

And as Ramsden et al. put it, rather dryly:

“This finding that greater lowering of serum cholesterol was associated with a higher rather than a lower risk of death in the MCE does not provide support for the traditional diet-heart hypothesis.” (Ramsden, 2016)

Surprisingly, the cholesterol–increased-mortality relationship was true in both the experimental and control groups; since even the controls increased their LA intake.

“Based on this increase in dietary linoleic acid alone, the Keys equation predicts that the control diet would lower average serum cholesterol compared with baseline (fig 3 and table 2). This reduction, however, would be modest compared with the reduction in the intervention group.” (Ramsden, 2016)

It’s a shame they didn’t just use the baseline as the control. It would have been most illuminating.

Frantz et al. tried various ways of finding a silver lining, but:

“None of these maneuvers changed the conclusions.” (Frantz, 1989)

“None of These Maneuvers Changed the Conclusions.”

So what did AHA & Co. do with these results? Having promoted the benefit of switching to polyunsaturated fats for CVD without any “final proof”:

“It must be emphasized that there is as yet no final proof that heart attacks or strokes will be prevented by such measures.” (Page, 1961)

AHA & Co. should have warned the nation—nay, the world—that their advice was not just baseless, but in error.

The MCE finished in 1973, and the results were reported in some form at an AHA conference in 1975 (Ramsden, 2010; Whorisky, 2016), but the impact was minimal enough that a paper written in 1977 by a critic of the AHA and the diet-heart hypothesis didn’t even mention it (Mann, 1977). A partial, peer-reviewed publication was delayed until 1989, a full 16 years after the study had finished, by which time the argument had been won, and the diet-heart hypothesis was firmly embedded in law and medicine. What’s worst is that we didn’t know about lowered cholesterol being correlated with higher mortality until 2016, when (Ramsden, 2016) was published, 43 years later.

Fans of the hypothesis have done their very best to ignore or deprecate the MCE, for obvious reasons.

“…part of the reason for the incomplete publication of the data might have been human nature. The Minnesota investigators had a theory that they believed in — that reducing blood cholesterol would make people healthier. Indeed, the idea was widespread and would soon be adopted by the federal government in the first dietary recommendations. So when the data they collected from the mental patients conflicted with this theory, the scientists may have been reluctant to believe what their experiment had turned up.

“‘The results flew in the face of what people believed at the time,’ said Broste [who had seen all the data]. ‘Everyone thought cholesterol was the culprit. This theory was so widely held and so firmly believed — and then it wasn’t borne out by the data. The question then became: Was it a bad theory? Or was it bad data? ... My perception was they were hung up trying to understand the results.’” (Whorisky, 2016)

Broste was a graduate student shortly after the study finished, and wrote his master’s thesis on this data. By the time that the results were fully published he had retired from a professional life.

This adds a bit of color to Jackson et al.’s otherwise innocuous statement:

The history of the AHA dietary fat recommendations from 1957 to 2015 has been published [9].

Needless to say, the AHA makes no mention whatsoever of the failed NDHS or MCE. Only (Page, 1961) is mentioned (AHA, 2015).

Now Back To That Epidemiology…

So when Jackson et al. assure us that the epidemiology shows us that LA is good for CVD risk, we must understand that this is only in the context of ignoring the higher-quality RCT evidence to the contrary.

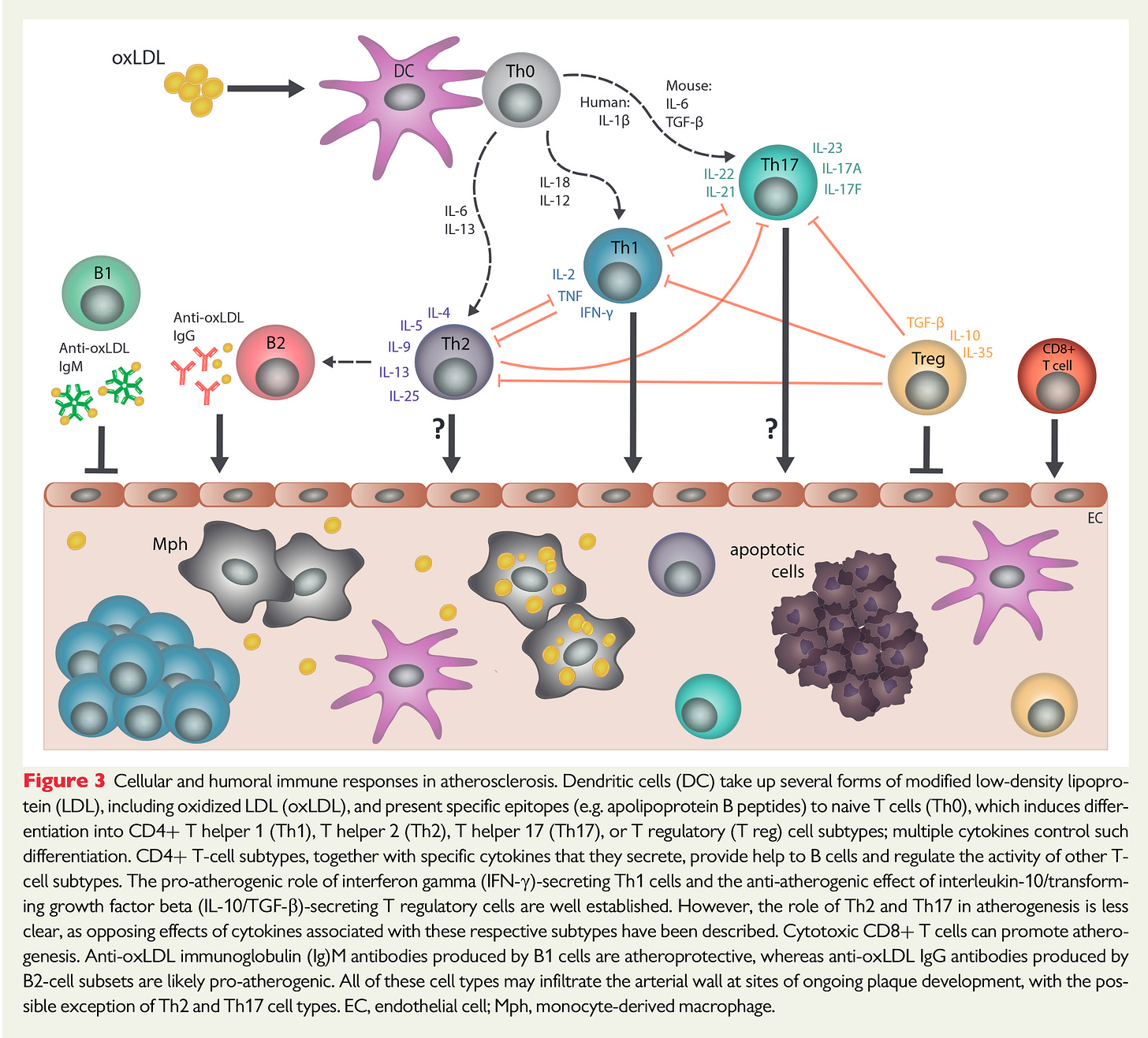

But that’s not all they ignore. For instance, they fail to discuss any evidence that indicates that CVD has gone up in the U.S. as LA increased, or that LA has been found to be causal in causing CVD, via its oxidation into toxins that are nearly universally recognized in the CVD literature, and that removing seed oils and replacing them with healthier oils prevents these toxins from forming (Boren, 2020; Guasch-Ferré, 2022; Reaven, 1991; Witztum, 1991).

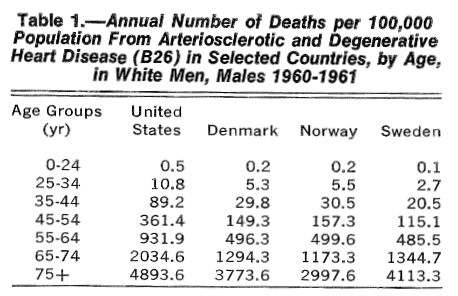

They ignore any epidemiology showing that CVD has been much lower in the past, in non-US nations around the world, and in immigrants to the U.S. (Bruhn, 1970; Cornfield, 1969; Lee, 1964; Thomas, 1957).

And they ignore that populations with near-zero rates of CVD are those that consume no seed oils (Cordain, 2002; Kaplan, 2017; Lindeberg, 1993; Mann, 1972).

They seem, in short, to ignore all evidence that might call their hypothesis into doubt.

A Short Note On Arachidonic Acid (AA)

I’m not going to go through all of their claims—it would take too long. But I wanted to address this one specifically, as it’s another core misdirection.

“Is there any utility to the n-6 to n-3 PUFA ratio?… Assumptions underlying the use of this ratio include… (4) that higher LA intakes lead to higher [AA] levels. None of these assumptions is correct, as we describe below.”

This is a surprising claim, as the senior author Calder recently observed that:

“It is true… that if you give people more linoleic acid you do tend to increase the arachidonic acid content of their cells.” (Hill, 2023, quote starts at 36:53)

He goes on to discuss some of the issues that might arise from a too-high level of AA, clearly he thinks it’s a worthy item for concern.

Nevertheless, in this paper it’s ultimately another misdirection. For CVD specifically, it has long been known that the problem is the consumption of LA via seed oils, not AA.

“In addition to a lowering in saturated fat intake, an increase in the consumption of vegetable oils, rich in (n-6) fatty acids such as linoleic acid, generally has been advocated. However, substituting saturated with polyunsaturated fats may not be advisable in light of recent evidence suggesting that oxidative modification of lipoproteins may enhance their atherogenic properties (Steinberg et al. 1989).” (Hennig, 1995)

In a follow-up paper to (Steinberg, 1989) the authors note:

“The importance of the fatty acid composition was impressively demonstrated by our recent studies of rabbits fed a diet high in linoleic acid (18:2) or in oleic acid (18:1) for a period of 10 wk. LDL isolated from the animals on oleic acid-rich diet were greatly enriched in oleate and low in linoleate. This LDL was remarkably resistant to oxidative modification, measured either by direct parameters of lipid peroxidation (i.e., TBARS and conjugated dienes) or by the indirect criterion of uptake by macrophages (53).” (Witztum, 1991)

They confirmed this experiment in humans (Reaven, 1991).

In a consensus paper issued by the European Atherosclerosis Society in 2020, (Steinberg, 1989) is cited and the oxidized LDL (oxLDL) they described shown as central to atherosclerosis (Boren, 2020).

So it’s been known since the 1990s that it is not AA that is the issue.

“Studies on tissue samples reveal that LA peroxidation products [the toxins] by far exceed those derived from arachidonic acid (AA) or any other PUFA.” (Spiteller, 1998)

You won’t read any of that in (Jackson, 2024), however.

Who Are These Authors?

I briefly discussed Kris-Etherton, a co-author of this paper, along with four others:

Kristina H. Jackson (first author)

William S. Harris

Martha A. Belury

Philip C. Calder (senior author)

Dr. Harris is a preeminent researcher of Ω-3 fats, was first author of the AHA’s 2009 paper, “Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention” (Harris, 2009a), and is the founder of the OmegaQuant company, which sells a well-regarded testing service for polyunsaturated fats. Dr. Kris-Etherton was also a co-author of (Harris, 2009a).

Dr. Jackson is Dr. Harris’ daughter, and is director of research for OmegaQuant. Having two daughters myself, I think that’s great.

Dr. Calder wrote a commentary on (Harris, 2007), titled, “The American Heart Association Advisory on n-6 Fatty Acids: Evidence Based or Biased Evidence?” (Calder, 2010). I’m frankly surprised to see him as senior author on this paper; he wrote the paper from which I got the graphic used on my X account. He was discussing liver disease in that paper, the mechanism of which is similar to that of CVD.

Dr. Belury is a registered dietician and nutritionist, and has been a professor of nutrition at a variety of schools. She has written a large number of papers expounding the benefits of linoleic acid on health. Enough so that I went and downloaded her CV—the 2018 version I found online was 39 pages long. She was chair and lead fundraiser for a symposium titled: “N-6 PUFA: They Are Not as Bad as You Think”, Dr. Harris was her co-conspirator in this enterprise (Belury, 2018). She’s president of the American Society for Nutrition. 90% of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee are members of the ASN (ASN Staff, 2023), so she’s as conventional as it’s possible to be.

In fact, they’re all the ‘elite’ of nutrition.

Blurring the Boundaries.

So what does their update tell us?

They’ve not taken any of the criticisms of their prior work to heart. Similar criticisms to mine have been made previously. (Harris, 2008), “Linoleic Acid and Coronary Heart Disease”, brought a letter from Drs. Ramsden, Hibbeln, and Lands:

“However, he failed to cite critical evidence that gives a deeper insight….

“Regrettably, Harris excluded two studies with increased cardiovascular events and mortality [3,4] and one that concluded that lower LA diets are more effective for CHD prevention [5].”

“The widespread consumption of diets with more than 2% energy as LA should be recognized for what it is—a massive uncontrolled human experiment without adequate rationales or proven mechanisms.” (Ramsden, 2009)

Harris replied with what I can best describe as several falsehoods, in my opinion. Most egregious was this:

“Ramsden et al are correct that Rose et al., [2] should have been included in the meta-analysis….

“Major coronary events occurred in 43%, 48% and 25% of each group, respectively.…

“…the most relevant comparison (between the two oil interventions) found no difference at all….

“Hence this study did not show increased CV events associated with LA intake as Ramsden et al. indicate.” (Harris, 2009b)

Yes, the two interventions were almost equally bad versus the control. But we do such comparisons compared to the control, not to the other treatment.

Why the need to misrepresent the Rose Corn Oil Trial?

“It is concluded that under the circumstances of this trial corn oil cannot be recommended in the treatment of ischaemic heart disease.” (Rose, 1965)

But he’s not done just yet.

“This paper is an abbreviated form of a review currently being prepared by the author and the following co-authors whose contributions are hereby gratefully acknowledged: Dariush Mozaffarian, Eric Rimm, Penny Kris-Etherton, Lawrence Rudel, Lawrence Appel, Marguerite Engler, Mary Engler, and Frank Sacks.” (Harris, 2009b)

That would be the afore-mentioned (Harris, 2009a), published as an official statement by the AHA, featuring two of the authors of (Jackson, 2024).

That brought forth further critical letters and a paper.

The first letter, from Ramsden, is titled “A Misrepresented Meta-analysis”:

“Regrettably, the recent AHA Advisory [1] relied heavily upon a one-line meta-analysis cited in a non peer-reviewed book chapter [2] to support its position that high intakes of omega6 fatty acids reduce CHD. Unfortunately, the credibility of this advisory is undermined by four additional critical errors….

“…2) Although the AHA Advisory [1] criticizes other studies for failing to distinguish between “distinct effects” of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, it commits this error throughout….” (Hibbeln, 2009)

Another letter:

“Harris et al.[1] cite a series of metabolic studies in which healthy men were fed a diet high in arachidonic acid (AA) and claim there was no evidence of harmful effects [2]. Yet, that’s not what the data show….

“The selective omission of this conclusion is especially troubling, given that most cases of myocardial infarction are due to the formation of an occluding thrombus on the surface of the arterial plaque….”

“AHA’s advisory continues the problematic trend identified by Tricoci et al [5], which found that a large proportion of recommendations in ACC/AHA guidelines are based on the lowest category of evidence, ‘expert’ opinion, in formulating guidelines with little empirical evidence. Health care professionals are well-advised to heed Tricoci’s recommendation--to exercise caution when considering guidelines not supported by solid evidence, which unfortunately is the case with this omega-6 PUFA advisory.” (Hibbeln, 2009)

There’s more in that reference, including Harris et al.’s response:

“…The perspectives reflected in these Letters to the Editor focus on relatively tangential observations that have too easily distracted from the central finding, a finding supported by a robust and coherent dataset that has accrued over decades, that omega‐6 FAs are cardioprotective….” (Hibbeln, 2009)

(Harris, 2009a) is written from the same playbook that informs (Jackson, 2024). Their mention of the MCE is confined to a reference:

Calling a failed trial not “significant” is a slight of hand. Increased mortality from a therapy is always significant, even if it is not statistically so.

A Critical Commentary

Discussing (Harris, 2009a):

“The AHA advisory evaluated the findings of nine RCT published from 1965 to 1989 and noted that at least five of these trials had design limitations; the latter limitations included the simultaneous use of plant or marine n-3 fatty acids in some studies. Although these limitations appear not to have been considered in developing the advisory, they may have influenced its major scientific conclusion (‘replacing saturated fatty acids with PUFAs lowered CHD events’), which is clearly not an n-6 fatty acid (or linoleic acid)-specific summary statement, and so somewhat blurs the boundaries between PUFA, n-6 PUFA and linoleic acid.”

That author contrasts the AHA’s sloppy approach to another paper:

“Ramsden et al. have evaluated the findings of studies specifically addressing the impact of increased linoleic acid intake separately from those that included linoleic acid in combination with n-3 fatty acids. Their efforts involved extensive detective work that included identification and use of food composition data from the locations and periods when several of the studies were performed, often over 40 years ago, and contacting original researchers of some of the older studies in order to clarify uncertain points.

“This scholarly approach, combined with the appreciations that (i) the terms PUFA and n-6 PUFA mean different things and (ii) linoleic acid alone and linoleic acid in combination with n-3 fatty acids may produce different findings, has yielded a different conclusion from the AHA advisory: ‘advice to specifically increase n-6 PUFA intake, based on mixed data, is unlikely to provide the intended benefits, and may actually increase the risks of CHD and death’. This piece of work by Ramsden et al. is to be applauded and will, it is hoped, open a healthy scientific debate on this important matter.” —Philip C. Calder

The paper was the aforementioned “The American Heart Association Advisory on n-6 Fatty Acids: Evidence Based or Biased Evidence?” (Calder, 2010), and he’s praising (Ramsden, 2010). Calder is the senior author of (Jackson, 2024).

He was once president of the International Society for the Study of Fatty Acids and Lipids (ISSFAL) of which Dr. Harris was a member.

That society actually convened a committee to look into the question of how much LA one should consume, and Harris had the opportunity to make his case, as this was the point of the exercise.

“On the basis of these results, we conclude that 2 energy % LA is adequate for healthy adult humans…. On the other hand, there are potential dangers associated with high LA intake.”

Nevertheless:

“These examples outline briefly the controversy as it stands regarding the health merits of LA intake above an adequate intake of 2 energy %. This committee recognises that some national bodies have already taken a stand and recommended a healthy upper limit for LA intake. At present, this committee could not reach consensus and has no recommendation to make on this question.” (ISSFAL, 2004)

Harris was evidently unable to convince his colleagues of the benefits of high LA consumption.

Conflicts of Interest

The second letter in (Hibbeln 2009), “From suggestion to admonition without direct data” is similarly critical, and contains the hilarious admonition:

“The advisory fails to inform the public that an important tissue indicator of CVD risk the ‘Omega-3 Index’, reflects the proportion of EPA and DHA in erythrocytes, a representative phospholipid eicosanoid precursor pool. The Omega-3 Index is regarded as superior to LDL as a biomarker predicting cardiovascular mortality.” (Hibbeln, 2009)

Of course Harris knows all about the Omega-3 Index, and Hibbeln would know it was Harris’ baby.

Harris had already, in 2008, started a company to monetize the Omega-3 Index, what is now known as OmegaQuant.

“The American Heart Association makes every effort to avoid any actual or potential conflicts of interest that may arise as a result of an outside relationship or a personal, professional, or business interest of a member of the writing panel. Specifically, all members of the writing group are required to complete and submit a Disclosure Questionnaire showing all such relationships that might be perceived as real or potential conflicts of interest.” (Harris, 2009a)

Oddly, there is no mention of OmegaQuant in the Disclosures section of (Harris, 2009a), despite Harris being one of two members of the LLC (which was dissolved and reincorporated with Harris as sole member and manager after (Harris, 2009a) was published).

You would think that having the AHA state officially that, “Although increasing omega-3 PUFA tissue levels does reduce the risk for CHD”, while citing Harris’ work, also an official statement of the AHA, would be a significant benefit to a start-up company whose business is testing omega-3 PUFA tissue levels.

Both Harris and Kris-Etherton do disclose a relationship with Unilever (as does one reviewer).

At the time a major manufacturer of commodity seed oils, Unilever have since divested that business but are still a major manufacturer of ultra-processed foods containing seed oils.

Mann stated:

“One of the originators of the diet-heart hypothesis, E.H. Ahrens, Jr., wrote in 1969 and has restated in recent Congressional testimony, ‘It is not proven that dietary modification can prevent arteriosclerotic heart disease in man.’ And yet the oil and spread industry advertises its products with claims and promises that make these foods seem like drugs.” (Mann, 1977)

While Unilever has divested its margarine brands, mayonnaise remains a major business:

“This not only making it the World’s No.1 mayonnaise brand[a] but also one of Unilever’s fastest-growing brands…”

The first ingredient in Hellman’s mayonnaise is soybean oil.

In (Jackson, 2024), the disclosure is brief:

“KHJ and WSH are part-owners of OmegaQuant Analytics LLC, a commercial lab specializing in fatty acid analysis. MAB has received funding from the United Soybean Board previously. PKE and PCC have no competing interests.”

Of course it would be good to have disclosed what type of fatty acid analysis OmegaQuant does, and that their idea that it’s not important to track the Ω-6/Ω-3 Ratio would be quite beneficial to their business.

Additionally, as we saw above, Harris has received funding from Unilever, as has Kris-Etherton (Harris, 2009a). Belury, according to her CV, was “Scientific Advisor, Dietary Spreads, Unilever Corporation, Consumer Foods Division, Germany” from 2007-2009 (Belury, 2018). Calder has received funding from Unilever (Calder, 2011), has been involved in the Nutrition in Transition group which is partially funded by Unilever (Calder, 2020a), and has co-written on essential fats including LA with Unilever employees (Calder, 2010).

While Unilever gets no mention in (Jackson, 2024), that doesn’t mean they don’t have influence. The FORCE enterprise discussed as a reliable source for information is funded in large part by Unilever.

I’m not a fan of the idea that corporations are the source of all evil in nutrition science. They’re clearly not.

But I think it’s pretty hard after reviewing the manifold conflicts of interest of these authors to view (Jackson, 2024) as anything other than a paid infomercial for the seed oil industry.

I’ll close with more from Philip Calder, from a 2020 review (Calder was ‘first author’) of the issues in therapeutic nutrition.

“Overall, a high exogenous supply of Ω-6 fatty acids may create a less optimal inflammatory, immunosuppressive, and coagulatory environment and can lead to poor outcomes.”

Note, this paper was not funded by Unilever.

It was funded and written by Fresenius Kabi Deutschland GmbH, which produces Omeganen, an Ω-3 fish oil product that has been shown to ameliorate the damage described above.

“Conflicts of interest: P. C. Calder has received speaker’s honoraria from Fresenius Kabi, B. Braun Melsungen, and Baxter Healthcare and has acted as an advisor to Fresenius Kabi and Baxter Healthcare.” (Calder, 2020b)

References

The Facts on Fats: 50 Years of American Heart Association Dietary Fats Recommendations. (2015, June). American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/-/media/files/healthy-living/company-collaboration/inap/fats-white-paper-ucm_475005.pdf

ASN Staff. (2023, January 20). 18 ASN Members Appointed to 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee—American Society for Nutrition. https://nutrition.org/18-asn-members-appointed-to-2025-dietary-guidelines-advisory-committee/

Baker, B. M., Frantz, I. D., Jr., Keys, A., Kinsell, L. W., Page, I. H., Stamler, J., & Stare, F. J. (1963). The National Diet-Heart Study: An Initial Report. JAMA, 185(2), 105–106. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1963.03060020065024

Bedigian, D., & Harlan, J. R. (1986). Evidence for Cultivation of Sesame in the Ancient World. Economic Botany, 40(2), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02859136

Belury, M. A., & Harris, W. S. (2018). Omega-6 fatty acids, inflammation and cardiometabolic health: Overview of supplementary issue. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 139, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2018.10.006

Blasbalg, T. L., Hibbeln, J. R., Ramsden, C. E., Majchrzak, S. F., & Rawlings, R. R. (2011). Changes in Consumption of Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acids in the United States During the 20th Century. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 93(5), 950–962. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.006643

Borén, J., Chapman, M. J., Krauss, R. M., Packard, C. J., Bentzon, J. F., Binder, C. J., Daemen, M. J., Demer, L. L., Hegele, R. A., Nicholls, S. J., Nordestgaard, B. G., Watts, G. F., Bruckert, E., Fazio, S., Ference, B. A., Graham, I., Horton, J. D., Landmesser, U., Laufs, U., … Ginsberg, H. N. (2020). Low-Density Lipoproteins Cause Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Pathophysiological, Genetic, and Therapeutic Insights: A Consensus Statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. European Heart Journal, 41(24), 2313–2330. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz962

Bruhn, J. G., & Wolf, S. (1970). Studies Reporting “Low Rates” of Ischemic Heart Disease: A Critical Review. American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health, 60(8), 1477–1495. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.60.8.1477

Calder, P. C., Dangour, A. D., Diekman, C., Eilander, A., Koletzko, B., Meijer, G. W., Mozaffarian, D., Niinikoski, H., Osendarp, S. J. M., Pietinen, P., Schuit, J., & Uauy, R. (2010). Essential fats for future health. Proceedings of the 9th Unilever Nutrition Symposium, 26–27 May 2010. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 64(S4), S1–S13. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2010.242

Calder, P. C. (2011). Editors’ conflicts of interest 2011. British Journal of Nutrition, 105(5), 661–662. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510005787

Calder, P. C., Feskens, E. J. M., Kraneveld, A. D., Plat, J., van ’t Veer, P., & de Vries, J. (2020). Towards “Improved Standards in the Science of Nutrition” through the Establishment of Federation of European Nutrition Societies Working Groups. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 76(1), 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506325

Christakis, G., Rinzler, S. H., Archer, M., & Kraus, A. (1966). Effect of the Anti-Coronary Club Program on Coronary Heart Disease Risk-Factor Status. JAMA, 198(6), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1966.03110190079022

Cordain, L., Eaton, S., Miller, J. B., Mann, N., & Hill, K. (2002). The Paradoxical Nature of Hunter-Gatherer Diets: Meat-Based, yet Non-Atherogenic. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 56(S1), S42–S52. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601353

Cornfield, J., & Mitchell, S. (1969). Selected Risk Factors in Coronary Disease. Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00039896.1969.10666860

Crowe, K. (2018, May 5). University of Twitter? Scientists give impromptu lecture critiquing nutrition research | CBC News [News]. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/second-opinion-alcohol180505-1.4648331

Grimshaw, R. (1889). Industrial Applications of Cottonseed Oil. Journal of the Franklin Institute, 127(3), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-0032(89)90146-4

Guasch-Ferré, M., Li, Y., Willett, W. C., Sun, Q., Sampson, L., Salas, -Salvadó Jordi, Mart, ínez-G. M. A., Stampfer, M. J., & Hu, F. B. (2022). Consumption of Olive Oil and Risk of Total and Cause-Specific Mortality Among U.S. Adults. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 79(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.10.041

Hamley, S. (2017). The effect of replacing saturated fat with mostly n-6 polyunsaturated fat on coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutrition Journal, 16(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-017-0254-5

Harcombe, Z., Baker, J. S., DiNicolantonio, J. J., Grace, F., & Davies, B. (2016). Evidence from Randomised Controlled Trials Does Not Support Current Dietary Fat Guidelines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Open Heart, 3(2), e000409. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2016-000409

Harris, W. S. (2008). Linoleic Acid and Coronary Heart Disease. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 79(3), 169–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2008.09.005

Harris, W. S., Mozaffarian, D., Rimm, E., Kris-Etherton, P. M., Rudel, L. L., Appel, L. J., Engler, M. M., Engler, M. B., & Sacks, F. (2009a). Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation, 119(6), 902–907. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191627

Harris, W. S. (2009b). Response to Letter to Editor Re: Linoleic Acid and Coronary Heart Disease. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 80(1), 77–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2008.12.003

Hennig, B., Toborek, M., Boissonneault, G. A., Shantha, N. C., Decker, E. A., & Oeltgen, P. R. (1995). Animal and plant fats selectively modulate oxidizability of rabbit LDL and LDL-mediated disruption of endothelial barrier function. The Journal of Nutrition, 125(8), 2045–2054. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/125.8.2045

Hill, S. (2023, September 11). What You Need to Know About Omega 3 and 6 Fats | Prof Philip Calder (No. 278) [Mp4]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bwdPhsKjU3o

Hooper, L. (2010). Meta-analysis of RCTs finds that increasing consumption of polyunsaturated fat as a replacement for saturated fat reduces the risk of coronary heart disease. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, 15(4), 108–109. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebm1093

Hooper, L., Martin, N., Abdelhamid, A., & Smith, G. D. (2015). Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011737

Hooper, L., Al‐Khudairy, L., Abdelhamid, A. S., Rees, K., Brainard, J. S., Brown, T. J., Ajabnoor, S. M., O’Brien, A. T., Winstanley, L. E., Donaldson, D. H., Song, F., & Deane, K. H. (2018). Omega‐6 Fats for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011094.pub3

Hooper, L., Martin, N., Jimoh, O. F., Kirk, C., Foster, E., & Abdelhamid, A. S. (2020). Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub2

Jackson, K. H., Harris, W. S., Belury, M. A., Kris-Etherton, P. M., & Calder, P. C. (2024). Beneficial Effects of Linoleic Acid on Cardiometabolic Health: An Update. Lipids in Health and Disease, 23(1), 296. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02246-2

Johns, D. M. (2023, April 13). Nutrition Science’s Most Preposterous Result: Could Ice Cream Possibly Be Good for You? The Atlantic, 5/2023. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2023/05/ice-cream-bad-for-you-health-study/673487/

Kaplan, H., Thompson, R. C., Trumble, B. C., Wann, L. S., Allam, A. H., Beheim, B., Frohlich, B., Sutherland, M. L., Sutherland, J. D., Stieglitz, J., Rodriguez, D. E., Michalik, D. E., Rowan, C. J., Lombardi, G. P., Bedi, R., Garcia, A. R., Min, J. K., Narula, J., Finch, C. E., … Thomas, G. S. (2017). Coronary atherosclerosis in indigenous South American Tsimane: A cross-sectional cohort study. The Lancet, 389(10080), 1730–1739. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30752-3

Lee, K. T., Nail, R., Sherman, L. A., Milano, M., Lee, K. T., Deden, C., Imai, H., Goodale, F., Nam, S. C., Lee, K. T., Goodale, F., Scott, R. F., Snell, E. S., Lee, K. T., Daoud, A. S., Jarmolych, J., Jakovic, L., & Florentin, R. (1964). Geographic Pathology of Myocardial Infarction: Part I. Myocardial infarction in orientals and whites in the United States; Part II. Myocardial infarction in orientals in Korea and Japan; Part III. Myocardial infarction in Africans in Africa and negroes and whites in the United States; Part IV. Measurement of amount of coronary arteriosclerosis in Africans, Koreans, Japanese and New Yorkers. The American Journal of Cardiology, 13(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(64)90219-X

Lindeberg, S., & Lundh, B. (1993). Apparent absence of stroke and ischaemic heart disease in a traditional Melanesian island: A clinical study in Kitava. Journal of Internal Medicine, 233(3), 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.1993.tb00986.x

Mann, G. V., Spoerry, A., Gray, M., & Jarashow, D. (1972). Atherosclerosis in the Masai. American Journal of Epidemiology, 95(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121365

Mann, G. V. (1977). Diet-Heart: End of an Era. New England Journal of Medicine, 297(12), 644–650. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM197709222971206

Mozaffarian, D., Micha, R., & Wallace, S. (2010). Effects on Coronary Heart Disease of Increasing Polyunsaturated Fat in Place of Saturated Fat: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS Medicine, 7(3), e1000252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000252

Mozaffarian, D., Hao, T., Rimm, E. B., Willett, W. C., & Hu, F. B. (2011). Changes in Diet and Lifestyle and Long-Term Weight Gain in Women and Men. New England Journal of Medicine, 364(25), 2392–2404. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1014296

Newport, M. T., & Dayrit, F. M. (2024). The Lipid–Heart Hypothesis and the Keys Equation Defined the Dietary Guidelines but Ignored the Impact of Trans-Fat and High Linoleic Acid Consumption. Nutrients, 16(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16101447

Rahn, R. F. (2008, November 24). Articles of Organization for OmegaQuant Analytics, LLC. State of South Dakota; Office of the Secretary of State, South Dakota. https://sosenterprise.sd.gov/BusinessServices/Business/ImageDownload.aspx?id=146091066111026094244252089123204030221194108182

Ramsden, C. E., Hibbeln, J. R., & Lands, W. E. (2009). Letter to the Editor re: Linoleic acid and coronary heart disease. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids (2008), by W.S. Harris. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 80(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2008.12.002

Ramsden, C. E., Hibbeln, J. R., Majchrzak, S. F., & Davis, J. M. (2010). n-6 fatty acid-specific and mixed polyunsaturate dietary interventions have different effects on CHD risk: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. The British Journal of Nutrition, 104(11), 1586–1600. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114510004010

Ramsden, C. E., Zamora, D., Leelarthaepin, B., Majchrzak-Hong, S. F., Faurot, K. R., Suchindran, C. M., Ringel, A., Davis, J. M., & Hibbeln, J. R. (2013). Use of Dietary Linoleic Acid for Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease and Death: Evaluation of Recovered Data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and Updated Meta-Analysis. BMJ, 346, e8707. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8707

Ramsden, C. E., Zamora, D., Majchrzak-Hong, S., Faurot, K. R., Broste, S. K., Frantz, R. P., Davis, J. M., Ringel, A., Suchindran, C. M., & Hibbeln, J. R. (2016). Re-Evaluation of the Traditional Diet-Heart Hypothesis: Analysis of Recovered Data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73). BMJ, 353. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1246

Reaven, P., Parthasarathy, S., Grasse, B. J., Miller, E., Almazan, F., Mattson, F. H., Khoo, J. C., Steinberg, D., & Witztum, J. L. (1991). Feasibility of Using an Oleate-Rich Diet to Reduce the Susceptibility of Low-Density Lipoprotein to Oxidative Modification in Humans. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 54(4), 701–706. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/54.4.701

Rose, G. A., Thomson, W. B., & Williams, R. T. (1965). Corn Oil in Treatment of Ischaemic Heart Disease. British Medical Journal, 1(5449), 1531–1533. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.5449.1531

Page, I. H., Stare, F. J., Corcoran, A. C., Pollack, H., & Wilkinson, C. F. (1957). Atherosclerosis and the Fat Content of the Diet. Circulation, 16(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.16.2.163

Skeaff, C. M., & Mann, J. I. (2016). Diet-heart disease hypothesis is unaffected by results of analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment. Evidence-Based Medicine, 21(5), 185. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2016-110486

Spiteller, G. (1998). Linoleic Acid Peroxidation—The Dominant Lipid Peroxidation Process in Low Density Lipoprotein—And Its Relationship to Chronic Diseases. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids, 95(2), 105–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-3084(98)00091-7

Thomas, W. A. (1957). Fatal Acute Myocardial Infarction: Sex, Race, Diabetes and Other Factors. Nutrition Reviews, 15(4), 97–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1957.tb00488.x

Whoriskey, P. (2016, April 13). This Study 40 Years Ago Could Have Reshaped the American Diet. But It Was Never Fully Published. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/04/12/this-study-40-years-ago-could-have-reshaped-the-american-diet-but-it-was-never-fully-published/

Witztum, J. L., & Steinberg, D. (1991). Role of Oxidized Low Density Lipoprotein in Atherogenesis. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 88(6), 1785–1792. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI115499

Sigh. So it turns out the "update" is .........sadly, more of the same.

Thanks for the review.

An incredible post.