Has "The Atlantic" Lost The Plot on Cooking Oil?

tldr: "Lost the Plot: If someone loses the plot, they become confused or crazy, or no longer know how to deal with a situation." *

Introduction

It’s kind of Yasmin Tayag to start with an ad hominem attack on people who don’t approve of our current cooking oil selections.

“Americans Have Lost the Plot on Cooking Oil” (or, if you don’t want to support them.)

Wow, she can’t even get out of the title without losing the plot!

“We seem to be entering a new era of yellow journalism, in which ad hominem attacks and conspiracy-mongering are more valued than truth and accuracy.” (Greenhut 2021)

It relieves me of the inclination to give her the benefit of the doubt.

But let’s go through the ‘facts’ she claims support her position first, as I’m old-fashioned, and will start there.

(All quotes will be from (Tayag, 2024), unless otherwise noted.)

To be clear, the claim she is disputing is that the Ω-6 fats, such as linoleic acid (LA) in which seed oils are rich, are unhealthy. They are often referred to as ‘cooking oil’ nowadays, as they are the predominant types of fats used in cooking and making foods.

Are “cooking oils” involved in health?

“Obsessing over the nutritional benefits of cooking oil won’t drastically improve anyone’s diet.”

As I have discussed many times, removing seed oils—the most common cooking oils—from my diet cured my 16-year bout of inflammatory bowel disease in two days. The association of seed oils and intestinal unrest is well-documented in the epidemiologic literature:

“The main finding of this study was more than a doubling of the risk of ulcerative colitis with the highest intake of the dietary Ω-6 PUFA, linoleic acid.”

“If the association is causative then 30% of all cases could be attributed to such higher intakes.” (IBD in EPIC Study Investigators et al., 2009, p. 1608)

My liver damage took a bit longer, four years, but it also was cured.

Cutting Ω-6 fats cures non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in short order, as this pilot study from Yale made clear.

“This study supports the concept that nutritional interventions might be most effective in ameliorating the metabolic phenotype of youth with NAFLD, providing additional benefits to dyslipidemia and insulin resistance not present in some drugs for treating NAFLD.” (Van Name, 2020)

Removing seed oils from my wife’s diet cured her fibromyalgia, after a three-decade battle with an incurable auto-immune disease, in a couple of months. Something none of her top physicians was able to accomplish.

We could go through other examples, notably the Lyon Diet-Heart Study (de Lorgeril 1994), but let’s save that for later.

Are seed oils part of “eating well”?

“In fact, at a certain point, it becomes a distraction from eating well.

“You can’t cook without oil or other kinds of fat—or, at least, cook well. Oil is primarily a vehicle for heat; without it, perfectly seared steak, caramelized onions, and crispy potatoes wouldn’t exist. Oil adds flavor too: Extra-virgin olive oil imparts richness to a caprese salad, and a drizzle of sesame oil transforms boiled greens into a savory side dish….”

This is the error of conflation: she is combining two unlike things in order to mislead one (perhaps even herself) into thinking they are the same thing.

Sadly, this is a common technique to mislead.

In this case, she is equating the delicious attributes of healthy, natural fats to those unhealthy fats recently added to the diet.

As we discussed recently with Chef Andrew Gruel, cooking with seed oils is in fact the inverse of “eating well”.

“Seed oils… they’re junk from a culinary perspective… It has no flavor, it tastes stale, and it tastes acrid—bitter.” (Goodrich, 2024)

Chef Gruel finds cooking with traditional fats, or with low-linoleic fats such as cultured oil, to be superior in taste to cooking with seed oils.

So do use olive oil, or sesame oil (as flavoring), or tallow in your cooking. Just avoid the seed oils.

And if what you are eating is making you sick and miserable, you are NOT “eating well”! This should be obvious.

Are saturated fats the problem?

Tayag cites four pieces of evidence, but all of them are from individuals associated with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (Giovannucci (Kim, 2021); Hu, Willett (Hu, 2001), (Zong, 2016); and Sacks (Sacks, 2017).

“But consuming certain oils and other kinds of fats can be harmful for your health.”

Citing: "Intake of Individual Saturated Fatty Acids and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Us Men and Women: Two Prospective Longitudinal Cohort Studies." (Zong, 2016)“One distinction matters most. Saturated fats, which tend to be solid at room temperature and include butter and lard, are linked to an increased risk of death from all causes, including heart disease and cancer.”

Citing: "Association Between Dietary Fat Intake and Mortality from All-Causes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies" (Kim, 2021)“Their unsaturated kin, usually liquid at room temperature and typically derived from plants, are considered far healthier, because they can lower cholesterol and reduce the risk of heart disease.”

Citing, “Types of Dietary Fat and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Critical Review” (Hu, 2001) and “Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association [AHA]” (Sack, 2017), respectively.

“I define journalistic objectivity as a genuine effort to be an honest broker when it comes to news. That means playing it straight without favoring one side when the facts are in dispute, regardless of your own views and preferences. It means doing stories that will make your friends mad when appropriate and not doing stories that are actually hit jobs or propaganda masquerading as journalism…. (Jones, 2009)

Hu and Willett specifically featured in this investigative post, in which I demonstrated how they misrepresented their own findings about seed oils and obesity to hide the fact that their own data showed seed oils are harmful:

What Is The Most Fattening Food?

I came across this paper recently: "Changes in Diet and Lifestyle and Long Term Weight Gain in Women and Men” (Mozaffarian et al., 2011) From the illustrious New England Journal of Medicine.Thanks for reading Tucker Goodrich: yelling Stop! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

As I noted in that post, both Hu and Willet held the title, ‘Frederick J. Stare Professor of Nutrition and Epidemiology’, in honor of a Harvard professor who biased his research results in exchange for funding from the sugar industry (Kearns, 2016; O’Conner, 2016).

Similarly, the paper I looked at was funded by the seed oil industry. Research from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health should be viewed with caution.

Tayag neglects to note that there is an ongoing dispute over the role of saturated fats and seed oils in health and in cardiovascular disease, in particular. She could have easily cited these four publications, to balance out those she presents above:

“Effects of Replacing Saturated Fat with Vegetable Oils Rich in Linoleic Acid on Coronary Heart Disease Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials”, (Ramsden, 2016a)

“Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies Evaluating the Association of Saturated Fat with Cardiovascular Disease”, (Siri-Tarino, 2010).

“Serial Measures of Circulating Biomarkers of Dairy Fat and Total and Cause-Specific Mortality in Older Adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study”, (de Oliveira, 2018).

“Saturated Fats and Health: A Reassessment and Proposal for Food-based Recommendations: JACC State-of -the-Art Review”, (Astrup, 2020).

To quote further from Jones:

“Often, there is information that does both, and that ambiguity needs to be reported with the same dispassion with which a scientist would report variations in findings that were inconclusive. If the evidence is inconclusive, then that is—by scientific standards—the truth.” (Jones, 2009)

Tayag doesn’t report on the evidence that might indicate that there is any issue with her argument. She is either not aware of the contrary evidence, or elects not to include it—she is doing “propaganda masquerading as journalism”; she is not reporting “the truth”. I’m going to assume it’s the latter, and we’ll discuss why later.

Are seed oils healthy?

“What we really want to do is replace the saturated fat in our diets with unsaturated fats,” Kris-Etherton said.”

Penny Kris-Etherton has written quite a bit about unsaturated fats and health. The AHA spent a lot of time and money trying to demonstrate that replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats would improve cardiovascular disease. They failed, but have never admitted to their failure (Newport, 2024—interview with Newport coming soon). It was later demonstrated that the crux of the process of cardiovascular disease is the oxidation of Ω-6 fats in seed oils, (Steinberg, 1989; Brown, 1990):

“The unsaturated fatty acids of the phospholipids are highly susceptible to chemical oxidation, which is prevented in plasma by antioxidants…. The LDL is then left to the mercy of oxygen radicals that convert the unsaturated fatty acids into reactive aldehydes and oxides that attach to lysines of apoB-100, mimicking acetylation. Such oxidized LDL is toxic to a variety of cells in vitro, and its importance in vivo has been dramatically underscored by three lines of evidence—first, antibodies against aldehyde-conjugated lysines stain atherosclerotic plaques; second, LDL from atherosclerotic plaques has an increased negative charge, binds to scavenger-cell receptors and produces foam cells in vitro; and third, probucol, an antioxidant, partially prevents atherosclerosis in Watanabe-heritable hyperlipidaemic rabbits, an animal counterpart of FH.” (Brown, 1990)

This remains the only explanation for the process of cardiovascular disease today (Borén, 2020).

While the process noted above was dependent on the oxidation of the Ω-6 fat linoleic acid, a French cardiologist noted that populations that had a higher consumption of the Ω-3 fat alpha-linolenic acid and lower levels of linoleic acid had lower rates of heart disease. Thus this was the core of the intervention he pursued in the afore-mentioned Lyon Diet-Heart Study (de Lorgeril, 1994), noting the research of Steinberg et al.:

“This could be due to … a lower intake of linoleic acid, easily oxidized in low density lipoproteins.” (de Lorgeril, 1994; referring to Reaven, 1993)

Lyon was so successful—a 70% decline in mortality in the intervention group—that the American Heart Association (AHA) took note. The initial 1994 report on Lyon was published in The Lancet, the British journal, but the final 1999 report was published in the AHA’s flagship journal Circulation (de Lorgeril, 1999).

This was followed by an “AHA Science Advisory: Lyon Diet Heart Study. Benefits of a Mediterranean-style, National Cholesterol Education Program/American Heart Association Step I Dietary Pattern on Cardiovascular Disease.” The primary author was Penny Kris-Etherton, who also was an author of the 2017 AHA Presidential advisory (Sacks, 2017).

“The unprecedented reduction in coronary recurrence rates, despite the fact that lipid/lipoprotein risk factors were comparable, clearly points to other important risk factor modifications as major influences in the development of CVD.” (Kris-Etherton, 2001)

While she notes the intervention included a lower intake of linoleic acid:

“Moreover, these subjects consumed less linoleic acid (3.6% versus 5.3% kcal) and more oleic acid (12.9% versus 10.8% kcal), alpha-linolenic acid (0.84% versus 0.29% kcal), and dietary fiber.” (Kris-Etherton, 2001)

Yet there is no specific discussion of altering Ω-6 fats as part of the intervention:

“Although the authors propose that alpha-linolenic acid plays an independent role in lowering CVD risk, other dietary differences between the experimental and control groups could account for the observed effects.” (Kris-Etherton, 2001)

And no mention whatsoever of the the role of linoleic acid in the oxidation of LDL, in the initiation or progression of CVD, or of the failure of the AHA’s attempt to show that increasing linoleic acid would reduce CVD (it increased it).

If you would think that increasing a factor increased disease, and reducing that factor was associated with a reduction in disease, might be of interest to the AHA, you would be mistaken.

Clearly Kris-Etherton is a participant on one side of this debate, and not an uninterested bystander.

However, Tayag presents no other side to this dispute.

“We’ve improved the fats in the U.S. food supply a lot in the last 20 years,” Walter Willett, a nutrition professor at Harvard, told me. “What’s left of the liquid plant oils are basically all healthy.”

This is an interesting, oddly-caveated quote, but again presented with no alternative viewpoint. One presumes that by “what’s left of the liquid plant oils” Willett is referring to the removal of trans-fats, in which he played a major role (Mozaffarian, 2006, 2009).

But what’s odd is that “basically all healthy” caveat.

Willett’s own work has shown that excess linoleic acid is “associated” with Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD), the leading cause of blindness in the U.S.; with increased obesity; and with increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Respectively:

“Dietary Fat and Risk for Advanced Age-Related Macular Degeneration”, (Seddon, 2001).

“Changes in Diet and Lifestyle and Long-Term Weight Gain in Women and Men”, (Mozaffarian, 2011).

“Associations Between Linoleic Acid Intake and Incident Type 2 Diabetes Among U.S. Men and Women”, (Zong, 2019).

I discussed the middle paper at length in the post "What is the Most Fattening Food" mentioned above (Goodrich, 2021), but a few choice quotes from the other two:

“Higher intake of specific types of fat—including vegetable, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats and linoleic acid—rather than total fat intake may be associated with a greater risk for advanced AMD. Diets high in ω-3 fatty acids and fish were inversely associated with risk for AMD when intake of linoleic acid was low”, (Seddon, 2001).

“Total [Ω-6] PUFAs were associated with a higher risk for type 2 diabetes in the age-adjusted model…” (Zong, 2019)

Amusingly, the authors of (Seddon, 2001), including Willet as senior author, puzzle over the the connection between CVD and AMD (blindness):

“Our results are noteworthy in light of the CVD hypothesis that AMD and CVD share some common risk factors… Long-chain Ω-3 fatty acids, especially docosahexanoic acid found primarily in fish, have been associated with an inverse risk for CVD in some studies. Our results suggest a similar trend for AMD, but only among individuals with lower intake of linoleic acid (an Ω-6 fatty acid). This latter finding supports other evidence in the literature that there may be a competition between Ω-3 and Ω-6 fatty acids and that both the level of Ω-3 fatty acids and its ratio to the Ω-6 fatty acids are important. Polyunsaturated fat is an important protective factor for CVD, but we observed a positive association between AMD and polyunsaturated fat intake in our data. It is possible that high intake of polyunsaturated fat may increase unsaturation of lipids in the macula and hence increase oxidative damage. We found no association between exudative AMD and dietary cholesterol, animal fat, and saturated fat, which are related to CVD.” (Seddon, 2001)

Of course, this ‘paradox’ is resolved if one takes the human RCT data discussed in (Ramsden, 2016a) and (de Lorgeril, 1994) into account, where a higher intake of Ω-3 fats was beneficial and increased Ω-6 fats was harmful (the latter showed a reduction is beneficial, which is the same thing).

Does this boil down to “basically all healthy”? Is Willett an uninterested bystander? Is any other view presented?

So are seed oils OK?

“Let this reassure you: Olive oil is always a good idea, but pretty much all other oils are too. Most plant-based oils contain so-called monounsaturated fatty acids and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which are genuinely good for you. (Maybe you’ve heard of the golden child of PUFAs: omega-3.)”

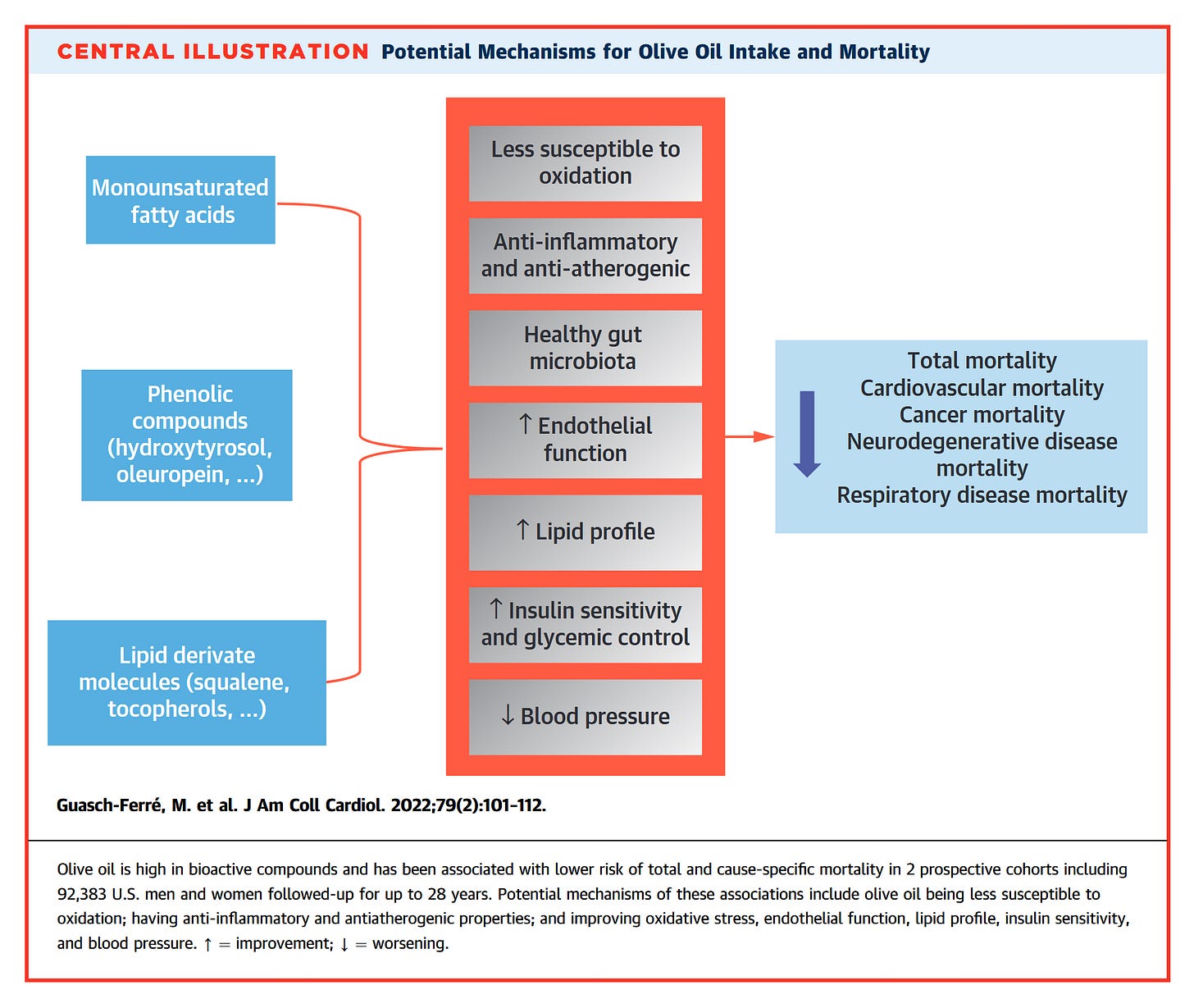

Funny, Willett & Co. recently released a study looking at the value of olive oil in health. Their central claim is that it’s beneficial—“lower risk of total and cause-specific mortality”—because it is “less susceptible to oxidization” and “anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic” (Guasch-Ferré, 2022).

Less than what? Why, than seed oils, of course. Many papers have found that the benefit of the monounsaturated fat in olive oil, oleic acid, is that it’s not susceptible to oxidation in the same way the Ω-6 PUFAs are (Borén, 2022; Brown, 1990; de Lorgeril, 1994; Reaven, 1993; Steinberg, 1989). And we’ll get to the “golden child” in a minute, but the benefit of that is ALSO that it’s less toxic than Ω-6 fats.

“Yes, even seed oils. Fears about these oils are fueled by another PUFA: omega-6, which has a complex link to inflammation. Because seed oils contain omega-6, detractors have claimed that cooking with them can cause many illnesses driven by inflammation, and that it competes with omega-3, diminishing the latter’s benefit. The reality is more nuanced: Omega-6 is associated with some inflammation, but consuming it is also linked to a reduced risk of heart disease and cancer.”

The paper is, "Association of Specific Dietary Fats With Total and Cause-Specific Mortality" (Wang, 2016); another Willett & Hu effort in creative epidemiology.

“Detractors”, like “deniers” is one of those unscientific pejoratives used when there’s evidence you don’t like which undercuts a position you hold.

In this case, we have “detractors” who point to the well-recognized scientific evidence of problems with Ω-6 fats.

So let’s review a little basic science here for Tayag, with her masters in biology.

We do science by coming up with hypotheses, and then gathering some data to see if this hypotheses pan out. Ideally, in human biology (her bachelors’ degree), we do an experiment or two to confirm that what we thought we saw is actually a causal mechanism. Epidemiology is a great and necessary way to come up with a hypothesis about what is happening.

A famous cautionary tale in epidemiology is the story of beta-carotene, the plant-based precursor to vitamin A. Epidemiology done by Willett and others showed a “link”, a statistical relationship that may or may not be cause-and-effect, between beta-carotene and lower incidence of cancer, which led them to attempt human trials of beta-carotene in cancer patients.

It didn’t go well.

The largest benefit was thought to occur in lung cancer, so they supplemented smokers with beta-carotene.

They turned out to be MORE likely to get lung cancer, not less.

This account comes from chapter 17, “Vitamin A and Lung Cancer” of Willet’s textbook, Nutritional Epidemiology (Willett, 2012)

In the case of seed oils and cardiovascular disease, we have a rather different scenario. The initial epidemiology and animal and human experimental work was done in the 1950s and ‘60s, and the human trials to confirm that increased seed oils would decrease CVD were started in the ‘60s and continued through the ‘70s. Those trials made it clear that the prescription for increased Ω-6 fats via seed oils as a preventative treatment for CVD was a failure, the principal investigator of the last, and biggest RCT said he was “disappointed” with the outcome (Taubes, 2008).

Despite a consistent pattern of failure of these trials (Newport, 2024; Ramsden, 2016a), ‘scientists’ such as Willett baselessly denigrate those trials, while ignoring the reality of the modern food system (Willett, 2016; Ramsden, 2016b).

Willett seems to have a double standard here. He does not advocate for beta-carotene supplementation after the failure of those trials, but he does advocate for continued consumption of high-Ω-6 seed oils after the failure of the AHA seed oil/CVD trials. Although, sotto voce, he concedes the problems with a high Ω-6 intake:

“The level of linoleic acid was well above the range recommended by the AHA; to get to this level the investigators created fake meat, cheese, and milk by removing the natural fats as much as possible and replacing these with corn oil. Whatever small amounts of Ω-3 fatty were present would have been removed.” (Willet, 2016)

The back-pedaling begins.

“It does compete with omega-3, but not significantly, Willett told me. Besides, framing these fatty acids as being in opposition is counterproductive. ‘We need both,’ he said.”

It’s indisputable that we need water, it’s also indisputable that too much water is harmful, and not just because of the risk of drowning. The same is true of oxygen. This is sophomoric reasoning, and one hopes this was an inaccurate paraphrasing of Willett’s view.

As far as it competing with Ω-3 “not significantly”, this is just false. If you are concerned about Ω-3 intake, as Willett says he is, the first thing you need to do is to cut Ω-6 intake. This has been known for a long time: “Dietary Omega-6 Fatty Acid Lowering Increases Bioavailability of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Human Plasma Lipid Pools”, (Taha, 2014):

“Dietary Ω-6 PUFA lowering for 12 weeks significantly reduces LA and increases Ω-3 PUFA concentrations… Findings in the [low Ω-6] group are consistent with previous reports showing that dietary LA lowering for 8–12 weeks in humans without concurrent increases in dietary Ω-3 PUFA significantly increased Ω-3 EPA, DPA and DHA concentrations in various circulating lipid pools [34, 18, 24].”

One begins to get the feeling that Tayag’s research for this article consisted of a phone interview with Willett and a lot of cut-and-pasting, without any effort to confirm what he said—a process known as fact-checking. “…Willett told me…” sounds a bit unconfident.

And now we go downhill.

“If any concern is worth paying attention to, it’s how to use oil well. Past its smoke point—the temperature at which an oil begins smoking—oil breaks down into harmful by-products. Overheating butter, which has one of the lowest smoke points of all cooking fats, leads to a kitchen full of fumes, and food that has potentially harmful compounds.”

Careful about that butter!

This is, again, just wrong. Smoke point is NOT an indicator of the healthfulness of an oil. Smoke point is an indicator of when an oil starts to smoke, and to soot up the interior of a dwelling. It’s an indicator of the relative quality of an oil used as a lamp oil.

“Smoke points have been used since about 1930 as a measurement of quality of kerosene used as an illuminating oil.”

Since:

“Smoke point is defined as the height in millimeters of the highest flame produced without smoking when the fuel is burned in a specified test lamp.” (Hunt, 1953)

So while it’s certainly useful to have less soot in the kitchen, if you are burning your oil you are no longer cooking.

“In the retail arena many people these days claim high smoke points without anybody really knowing what this means” (Eyres, 2015).

That’s exactly what Tayag is doing.

What is a useful indicator of how unhealthy an oil is? Why, how much polyunsaturated fats are in the oil. In fact, higher linoleic acid in an oil decreases the smoke point, and decreases the healthfulness of the oil by increasing it’s tendency to go rancid (Eyres, 2013; Grootveld, 2014; Hunt, 1953).

Even heating an oil high in polyunsaturated fats under the smoke point is harmful. In an experiment looking at cooking oils below the smoke point of many oils, 356F (180C), Grootveld et al. found:

“As expected, the levels of total aldehydes generated increase proportionately with oil PUFA content, and over half are the more highly cytotoxic α,β-unsaturated classes, which include acrolein and 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal (HNE), as well as 4-hydroperoxy-, 4-hydroxy-, and 4,5-epoxy-trans-2-alkenals.” (Grootveld, 2014)

These aldehydes are toxic, they are implicated in all the major chronic diseases and causes of death. And they’re not just harmful when they are ingested:

“The concentrations of aldehydes generated in culinary oils during episodes of heating at 180°C represent only what remains in the oil: Owing to their low boiling points, many of the aldehydes generated are volatilized at standard frying temperatures. These represent inhalation health hazards, in view of their inhalation by humans, especially workers in inadequately ventilated fast-food retail outlets.” (Grootveld, 2014)

Inhalation of these toxic aldehydes from frying with seed oils is why the World Health Organization has found them to be a known animal carcinogen, and a probable human carcinogen (Straif, 2006; IARC, 2010).

Sadly, the WHO points the finger at the “golden child”, the Ω-3 fats in seed oils, as being the most carcinogenic component of these oils, an assessment confirmed by the U.S. Federal Government’s National Toxicology Program (NTP, 2003).

This is why we have a pandemic of lung cancer in women who have never smoked.

“In this international study, the authors found that, while lung-cancer rates have declined among younger men, they are rising among younger women, despite the fact that these women are not smoking more than men.” (Fidler-Benaoudia, 2020)

“Using the right oil for deep-frying might avoid creating carcinogenic compounds, but it won’t negate the health impacts of eating deep-fried foods.”

Note that she concedes that these lipid oxidation products (LOPs) are known to be carcinogenic! Which suggests she’s aware of the negative health effects of these oils, but is electing not to discuss it (such a sloppy mistake!).

But, this is not just a problem with deep-frying:

Our experiments have shown that shallow frying gives rise to much higher levels of LOPs than deep frying under the same conditions (reflecting the influence of the surface area of the frying medium, its exposure to atmospheric O2, and the subsequent dilution of LOPs generated into the bulk medium). (Grootveld, 2014)

The “health impacts of eating deep-fried foods” are almost entirely due to the oxidization of PUFA (IARC, 2011; Grootveld, 2014; NTP, 2003; Straif, 2006).

It’s easy to measure the degradation of oils during cooking. You measure the decline in the easily-oxidized fats.

“Absolute content of polyunsaturated fatty acid, such as linoleic acid, reduced more than that of monounsaturated fatty acid, such as oleic acid, in both oils” (Yoon, 1987).

Conclusion

“Unless every other aspect of your diet has been optimized to be as nutritious as possible, it probably doesn’t matter if you exclusively cook with extra-virgin olive oil that’s cold-pressed, unfiltered, and imported straight from a pristine Greek island.”

This is very misleading. The single biggest change in the human diet in the last century or so—depending on where you live—is the increased consumption of seed oils.

“At this stage, vegetable oils contribute far more energy to the human food supply than do meat or animal fats” (Drewnowski, 1997)

In the U.S., consumption of “added plant-based fats and oils” has reached >21% of our calories consumed (Rehkamp, 2016).

This has been a massive change over the last century or so in the U.S.

If Willett and his co-ideologues were correct and increased consumption of PUFA from seed oils are essential to human health, then the U.S. should be the healthiest country on Earth.

In fact, we are plagued by chronic diseases linked to seed oils.

It should be no surprise.

Tayag has a history of providing one-sided information masking as journalism. During the COVID-19 Pandemic, she was lead editor of the Medium’s COVID-19 blog, which was a similarly biased enterprise, as a quick review of the posts will make clear.

What Tayag and the Atlantic have engaged in is not objective, well-researched journalism, it’s propaganda—a press-release for the seed oil industry, aided and abetted by an institution renowned for taking money in exchange for biased research (Kearns, 2016; O’Conner, 2016).

References

Astrup, A., Magkos, F., Bier, D. M., Brenna, J. T., de Oliveira Otto, M. C., Hill, J. O., King, J. C., Mente, A., Ordovas, J. M., Volek, J. S., Yusuf, S., & Krauss, R. M. (2020). Saturated Fats and Health: A Reassessment and Proposal for Food-based Recommendations: JACC State-of -the-Art Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 76(7), 844–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.077

Borén, J., Chapman, M. J., Krauss, R. M., Packard, C. J., Bentzon, J. F., Binder, C. J., Daemen, M. J., Demer, L. L., Hegele, R. A., Nicholls, S. J., Nordestgaard, B. G., Watts, G. F., Bruckert, E., Fazio, S., Ference, B. A., Graham, I., Horton, J. D., Landmesser, U., Laufs, U., … Ginsberg, H. N. (2020). Low-Density Lipoproteins Cause Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Pathophysiological, Genetic, and Therapeutic Insights: A Consensus Statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. European Heart Journal, 41(24), 2313–2330. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz962

Brown, M. S., & Goldstein, J. L. (1990). Scavenging for Receptors. Nature, 343(6258), 508–509. https://doi.org/10.1038/343508a0

de Lorgeril, M., Renaud, S., Mamelle, N., Salen, P., Martin, J. L., Monjaud, I., Guidollet, J., Touboul, P., & Delaye, J. (1994). Mediterranean Alpha-Linolenic Acid-Rich Diet in Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease. Lancet (London, England), 343(8911), 1454–1459. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92580-1

de Lorgeril, M., Salen, P., Martin, J. L., Monjaud, I., Delaye, J., & Mamelle, N. (1999). Mediterranean Diet, Traditional Risk Factors, and the Rate of Cardiovascular Complications After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation, 99(6), 779–785. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.99.6.779

de Oliveira Otto, M. C., Lemaitre, R. N., Song, X., King, I. B., Siscovick, D. S., & Mozaffarian, D. (2018). Serial Measures of Circulating Biomarkers of Dairy Fat and Total and Cause-Specific Mortality in Older Adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 108(3), 476–484. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy117

Eyres, L. (2015). Frying Oils: Selection, Smoke Points and Potential Deleterious Effects for Health. Food New Zealand, 15(1), 30–31. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.131757870182463

Drewnowski, A., & Popkin, B. M. (1997). The Nutrition Transition: New Trends in the Global Diet. Nutrition Reviews, 55(2), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01593.x

Fidler-Benaoudia, M. M., Torre, L. A., Bray, F., Ferlay, J., & Jemal, A. (2020). Lung Cancer Incidence in Young Women Vs. Young Men: A Systematic Analysis in 40 Countries. International Journal of Cancer, 147(3), 811–819. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32809

Guasch-Ferré, M., Li, Y., Willett, W. C., Sun, Q., Sampson, L., Salas, -Salvadó Jordi, Mart, ínez-G. M. A., Stampfer, M. J., & Hu, F. B. (2022). Consumption of Olive Oil and Risk of Total and Cause-Specific Mortality Among U.S. Adults. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 79(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.10.041

Goodrich, T. (2021, October 19). What Is The Most Fattening Food? [Blog]. Yelling Stop. https://tuckergoodrich.substack.com/p/what-is-the-most-fattening-food

Goodrich, T. (2024, February 2). Ep. 13: Chef Andrew Gruel: Learning to Cook Again—with Dr. Brian Kerley [Substack newsletter]. Tucker Goodrich: Yelling Stop. https://tuckergoodrich.substack.com/p/ep-12-chef-andrew-gruel-learning

Greenhut, S. (2021, December 17). Why Are So Many Prominent Journalists Abandoning Journalism? Reason.Com. https://reason.com/2021/12/17/why-are-so-many-prominent-journalists-abandoning-journalism/

Grootveld, M., Rodado, V. R., & Silwood, C. J. L. (2014). Detection, Monitoring, and Deleterious Health Effects of Lipid Oxidation Products Generated in Culinary Oils During Thermal Stressing Episodes. INFORM Magazine, 25(10), 614–624.

Hu, F. B., Manson, J. E., & Willett, W. C. (2001). Types of Dietary Fat and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Critical Review. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 20(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2001.10719008

Hunt, R. A. (1953). Relation of Smoke Point to Molecular Structure. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 45(3), 602–606. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie50519a039

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. (2010). Household Use of Solid Fuels and High-Temperature Frying (Vol. 95). International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Monographs-On-The-Identification-Of-Carcinogenic-Hazards-To-Humans/Household-Use-Of-Solid-Fuels-And-High-temperature-Frying-2010

IBD in EPIC Study Investigators, Tjonneland, A., Overvad, K., Bergmann, M. M., Nagel, G., Linseisen, J., Hallmans, G., Palmqvist, R., Sjodin, H., Hagglund, G., Berglund, G., Lindgren, S., Grip, O., Palli, D., Day, N. E., Khaw, K.-T., Bingham, S., Riboli, E., Kennedy, H., & Hart, A. (2009). Linoleic Acid, a Dietary N-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid, and the Aetiology of Ulcerative Colitis: A Nested Case-Control Study Within a European Prospective Cohort Study. Gut, 58(12), 1606–1611. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2008.169078

Jones, A. (2009, September 15). An Argument Why Journalists Should Not Abandon Objectivity [Advertisement]. Nieman Foundation. https://nieman.harvard.edu/articles/an-argument-why-journalists-should-not-abandon-objectivity/. Excerpt from: Jones, A. (2011). Losing the News: The Future of the News that Feeds Democracy (Reprint edition). Oxford University Press. https://amzn.to/4eJpz38

Kearns, C. E., Schmidt, L. A., & Glantz, S. A. (2016). Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research: A Historical Analysis of Internal Industry Documents. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(11), 1680–1685. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394

Kim, Y., Je, Y., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2021). Association between dietary fat intake and mortality from all-causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland), 40(3), 1060–1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2020.07.007

Kris-Etherton, P. M., Eckel, R. H., Howard, B. V., Jeor, S. C. S., & Bazzarre, T. L. (2001). AHA Science Advisory: Lyon Diet Heart Study. Benefits of a Mediterranean-style, National Cholesterol Education Program/American Heart Association Step I Dietary Pattern on Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation, 103(13), 1823–1825. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.103.13.1823

Lee, J. H., Duster, M., Roberts, T., & Devinsky, O. (2022). United States Dietary Trends Since 1800: Lack of Association Between Saturated Fatty Acid Consumption and Non-communicable Diseases. Frontiers in Nutrition, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.748847

Mozaffarian, D., Katan, M. B., Ascherio, A., Stampfer, M. J., & Willett, W. C. (2006). Trans Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(15), 1601–1613. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra054035

Mozaffarian, D., Aro, A., & Willett, W. C. (2009). Health effects of trans -fatty acids: Experimental and observational evidence. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 63(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602973

NATIONAL TOXICOLOGY PROGRAM. (2003, October). Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of 2,4-Hexadienal in F344/N Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Gavage Studies). U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health. https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/publications/reports/tr/500s/tr509/index.html?utm_source=direct&utm_medium=prod&utm_campaign=ntpgolinks&utm_term=tr509abs

Newport, M. T., & Dayrit, F. M. (2024). The Lipid–Heart Hypothesis and the Keys Equation Defined the Dietary Guidelines but Ignored the Impact of Trans-Fat and High Linoleic Acid Consumption. Nutrients, 16(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16101447

O’Connor, A. (2016, September 12). How the Sugar Industry Shifted Blame to Fat. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/13/well/eat/how-the-sugar-industry-shifted-blame-to-fat.html

Ramsden, C. E., Zamora, D., Majchrzak-Hong, S., Faurot, K. R., Broste, S. K., Frantz, R. P., Davis, J. M., Ringel, A., Suchindran, C. M., & Hibbeln, J. R. (2016a). Re-Evaluation of the Traditional Diet-Heart Hypothesis: Analysis of Recovered Data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73). BMJ, 353, Appendix A, Part 2. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1246

Ramsden, C. E., Zamora, D., Majchrzak-Hong, S. F., Faurot, K. R., Broste, S. K., Frantz, R. P., Davis, J. M., Ringel, A., Suchindran, C. M., & Hibbeln, J. R. (2016b). Re: Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73). BMJ, 2016(353), i1246. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1246

Reaven, P., Parthasarathy, S., Grasse, B. J., Miller, E., Steinberg, D., & Witztum, J. L. (1993). Effects of Oleate-Rich and Linoleate-Rich Diets on the Susceptibility of Low Density Lipoprotein to Oxidative Modification in Mildly Hypercholesterolemic Subjects. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 91(2), 668–676.

Rehkamp, S. (2016, December 5). A Look at Calorie Sources in the American Diet [Propaganda]. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2016/december/a-look-at-calorie-sources-in-the-american-diet/

Seddon, J. M., Rosner, B., Sperduto, R. D., Yannuzzi, L., Haller, J. A., Blair, N. P., & Willett, W. (2001). Dietary Fat and Risk for Advanced Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Archives of Ophthalmology, 119(8), 1191–1199. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.119.8.1191

Sacks Frank M., Lichtenstein Alice H., Wu Jason H.Y., Appel Lawrence J., Creager Mark A., Kris-Etherton Penny M., Miller Michael, Rimm Eric B., Rudel Lawrence L., Robinson Jennifer G., Stone Neil J., & Van Horn Linda V, on behalf of the American Heart Association. (2017). Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 136(3), e1–e23. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510

Siri-Tarino, P. W., Sun, Q., Hu, F. B., & Krauss, R. M. (2010). Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies Evaluating the Association of Saturated Fat with Cardiovascular Disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(3), 535–546. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.27725

Steinberg, D., Parthasarathy, S., Carew, T. E., Khoo, J. C., & Witztum, J. L. (1989). Beyond Cholesterol. Modifications of Low-Density Lipoprotein That Increase Its Atherogenicity. The New England Journal of Medicine, 320(14), 915–924. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198904063201407

Straif, K., Baan, R., Grosse, Y., Secretan, B., El Ghissassi, F., Cogliano, V., & WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. (2006). Carcinogenicity of Household Solid Fuel Combustion and of High-Temperature Frying. The Lancet Oncology, 7(12), 977–978. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(06)70969-x

Taha, A. Y., Cheon, Y., Faurot, K. F., MacIntosh, B., Majchrzak-Hong, S. F., Mann, J. D., Hibbeln, J. R., Ringel, A., & Ramsden, C. E. (2014). Dietary Omega-6 Fatty Acid Lowering Increases Bioavailability of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Human Plasma Lipid Pools. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, and Essential Fatty Acids, 90(5), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2014.02.003

Tayag, Y. (2024, June 21). Americans Have Lost the Plot on Cooking Oil. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2024/06/olive-oil-canola-cooking/678761/

Van Name, M. A., Savoye, M., Chick, J. M., Galuppo, B. T., Feldstein, A. E., Pierpont, B., Johnson, C., Shabanova, V., Ekong, U., Valentino, P. L., Kim, G., Caprio, S., & Santoro, N. (2020). A Low ω-6 to ω-3 PUFA Ratio (n–6:n–3 PUFA) Diet to Treat Fatty Liver Disease in Obese Youth. The Journal of Nutrition, 150(9), 2314–2321. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxaa183

Wang, D. D., Li, Y., Chiuve, S. E., Stampfer, M. J., Manson, J. E., Rimm, E. B., Willett, W. C., & Hu, F. B. (2016). Association of Specific Dietary Fats With Total and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(8), 1134–1145. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2417

Willett, W. (2012). Nutritional Epidemiology. Oxford University Press.

Willett, W. C. (2016). Re: Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73). BMJ, 2016(353), i1246. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1246

Yoon, S. H., Kim, S. K., Kim, K. H., Kwon, T. W., & Teah, Y. K. (1987). Evaluation of Physicochemical Changes in Cooking Oil During Heating. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 64(6), 870–873. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02641496

Zong, G., Li, Y., Wanders, A. J., Alssema, M., Zock, P. L., Willett, W. C., Hu, F. B., & Sun, Q. (2016). Intake of Individual Saturated Fatty Acids and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Us Men and Women: Two Prospective Longitudinal Cohort Studies. BMJ, 355, i5796. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5796

Zong, G., Liu, G., Willett, W. C., Wanders, A. J., Alssema, M., Zock, P. L., Hu, F. B., & Sun, Q. (2019). Associations Between Linoleic Acid Intake and Incident Type 2 Diabetes Among U.S. Men and Women. Diabetes Care, 42(8), 1406–1413. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-0412

To what end is The Atlantic putting out shit like this? IMO, it's part of a push to portray ANY straying from the "mainstream" of the Health Industrial Complex as "right wing". Don't want to just eat bugs, plants and seed oils? RIGHT WING. Raw milk? RIGHT WING. Pay attention to your body and working out? RIGHT WING. Don't blandly trust the advice of doctors to put more pills into your body? RIGHT WING. Don't want to just unthinkingly give your 15 year old daughters hormonal birth control? RIGHT WING etc etc

I say we encourage this woman to take her own advice for another ten years, then, if she is still alive and cognisant, gently request to see her biomarkers. Good luck to her.