Quick Study Analysis: "Butter and Plant-Based Oils Intake and Mortality"

tl;dr: More baloney from the baloney factory.

This is pretty ironic timing: just as Robert F. Kennedy Jr. takes over the Department of Health and Human Services, which includes the NIH, with a pledge to, among other things, get seed oils out of the food supply: the biggest seed-oil cheerleaders on Earth come out with yet another bogus study to convince us of the benefits of rancid fats .

This study, funded almost entirely by the NIH, may be the perfect example of what’s wrong with the NIH funding process.

So what did we get for our tax-payer’s dollars?

First, let’s consider the data (Quotes from (Zhang, 2025) are bolded).

They used three previously-conducted epidemiological studies: “Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII), and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS).”:

“Participants… reporting implausible energy intake (total energy intake <500 or >3500 kcal/d for women and <800 or >4200 kcal/d for men) were excluded from the analysis.”

Got that? According to the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH), it’s plausible that people could live on 501 or 801 calories, for decades.

This isn’t a new observation, in fact it’s one I’ve made before:

And here:

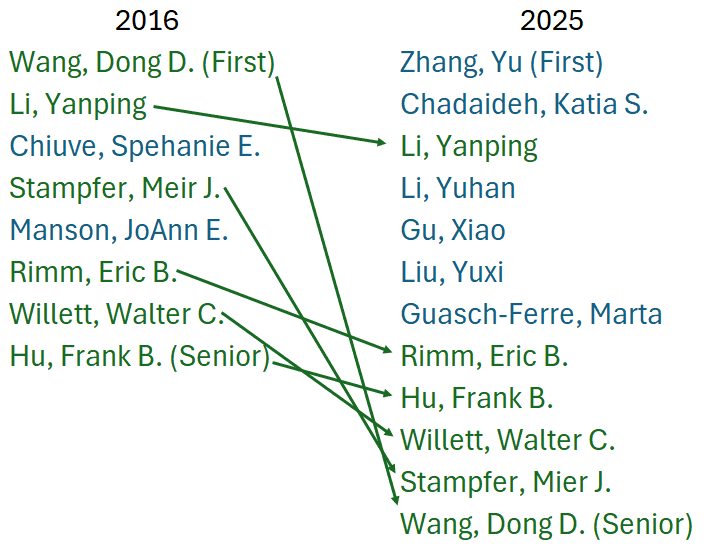

Note that language is almost identical, even though the primary author is different (Wang, 2016). But let’s also notice some significant overlap. Dong D. Wang, the first author of the 2016 paper is now the senior author for the 2025 paper.

And note the similarity in the titles: “Association of Specific Dietary Fats With Total and Cause-Specific Mortality” (Wang, 2016). One suspects that they just updated the earlier effort, with a lot of cut-and-paste and verbiage modification to avoid the sin of self-plagiarization.

Let’s also notice that for some inexplicable reason, the 2016 paper set the limit for women at 600 calories, but for 2025 they’ve lowered that to 500 calories. Did they discover a population of American women living on between 501 and 600 calories in the intervening nine years?

I owe this observation about bogus levels of calories to Edward Archer, who analyzed the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, and discovered that the majority of the people surveyed, using a measure similar to that used this these studies (dietary recall survey), reported implausible numbers.

Note, this doesn’t mean that what they reported was accurate, or reflected their actual intake, just that it’s plausible, meaning that what they reported could sustain life.

Archer concludes:

“As such, there are no valid population-level data to support speculations regarding trends in caloric consumption and the etiology of the obesity epidemic. Because under-reporting and physiologically implausible rEI values are a predominant feature of U.S. nutritional surveillance, the ability to generate empirically supported public policy and dietary guidelines relevant to the obesity epidemic based on these data is extremely limited.” (Archer, 2013)

Ten years later, another group of researchers looked at the same question, and found:

“We applied the equation to two large datasets (National Diet and Nutrition Survey and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) and found that the level of misreporting was >50%. The macronutrient composition from dietary reports in these studies was systematically biased as the level of misreporting increased, leading to potentially spurious associations between diet components and body mass index.” (Bajunaid, 2025)

The senior author on that effort was John Speakman.

While the three surveys here are different from those analyzed above, they are subject to the same flaws.

And they know this.

“First, dietary data from [Food Frequency Questionnaires] and other methods are affected by measurement errors…”

Having spent a lot of time on data integrity issues over the years, I can observe that there is no way to adjust or fix data that comes from a bogus data-collection methodology. In this case specifically, there’s no reference data source that one can go to to correct the data, the entire dataset must be considered invalid.

"Nutritional epidemiology is a scandal, it should just go to the waste bin."—John Ioannidis (Crowe, 2018)

But, of course, binning the database would put the Harvard School of Public Health out of business.

So they just admit that their data is bogus, since no-one can live on 501, 601, or even 801 calories, and they rely on gullible medical professionals and journalists to spread the word. And, of course, the NIH to fund it.

So I’m not even going to waste our time on going through their detailed analysis. Garbage in still results in garbage out.

A few other observations about duplicitous behavior: you may be shocked to learn this, but these are not the first people to look at this question, either in 2016 or 2025.

The question of whether or not “plant-based oils” have health benefits has been litigated an nauseum. The general scheme of science is that one does epidemiology like this to see if there’s a signal that may indicate that X causes Y, and then one does an experimental intervention (ideally a randomized controlled trial) to determine if X truly does cause Y.

Perhaps the largest review of the evidence was done by the Cochrane Collaboration, in a 890-page opus (Abdelhamid, 2020; Hoper, 2018; Hooper, 2020) that largely boils down to “little or no difference” (a phrase used 14 times):

“Increasing omega-6 fats may make little or no difference to all-cause mortality or CVD events (low-quality evidence), and we are uncertain of effects on CVD mortality, coronary heart disease, MACCEs and stroke (very low-quality evidence).” (Hooper, 2020)

Long-time followers of HSPH will not be surprised to learn that the Cochrane studies are not mentioned. Instead, they rely on an older study, (Sacks 2017), from the American Heart Association (AHA):

“Previous randomized clinical trials have shown that incorporating soybean oil into the diet, especially as a substitute for butter, can lower circulating cholesterol levels and reduce the risk of coronary heart disease and total mortality.44,45” (Zhang, 2025)

(Sacks 2017) is their ref. 44.

I discussed it in this post:

So what’s the distinction between Sacks and Hooper?

“The implications of the reviews are different, but related: Hooper 2015 and Sacks 2017 suggest that reducing saturated fat and replacement by polyunsaturated fats reduces the risk of CVD events, while the present review suggests that increasing omega-6 fats may reduce the risk of myocardial infarction, but we did not find evidence of an effect on CVD events.” (Hooper, 2020)

And even worse:

“Primary outcomes: we found low-quality evidence that increased intake of omega-6 fats may make little or no difference to all-cause mortality (risk ratio (RR) 1.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.88 to 1.12, 740 deaths, 4506 randomised, 10 trials) or CVD events (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.15, 1404 people experienced events of 4962 randomised, 7 trials).” (Hooper, 2020)

What that means is that you are less likely to have a heart attack, but it is more likely to kill you. Ironically, this is what the AHA’s very first RCT on the topic found, where while the control group had more ‘events’, it had lower mortality, “This does appear somewhat unusual…” (Christakis, 1966).

Why might they do such cherry-picking? Standard scientific practice is to favor more recent and comprehensive work, especially when done by a group as prestigious as Cochrane. But then they wouldn’t be able to say:

“The present findings are closely aligned with the dietary recommendations of the American Heart Association and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans,53 which advocate for reducing saturated fat intake and replacing it with polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats to lower the risk of chronic disease.44” (Zhang, 2025).

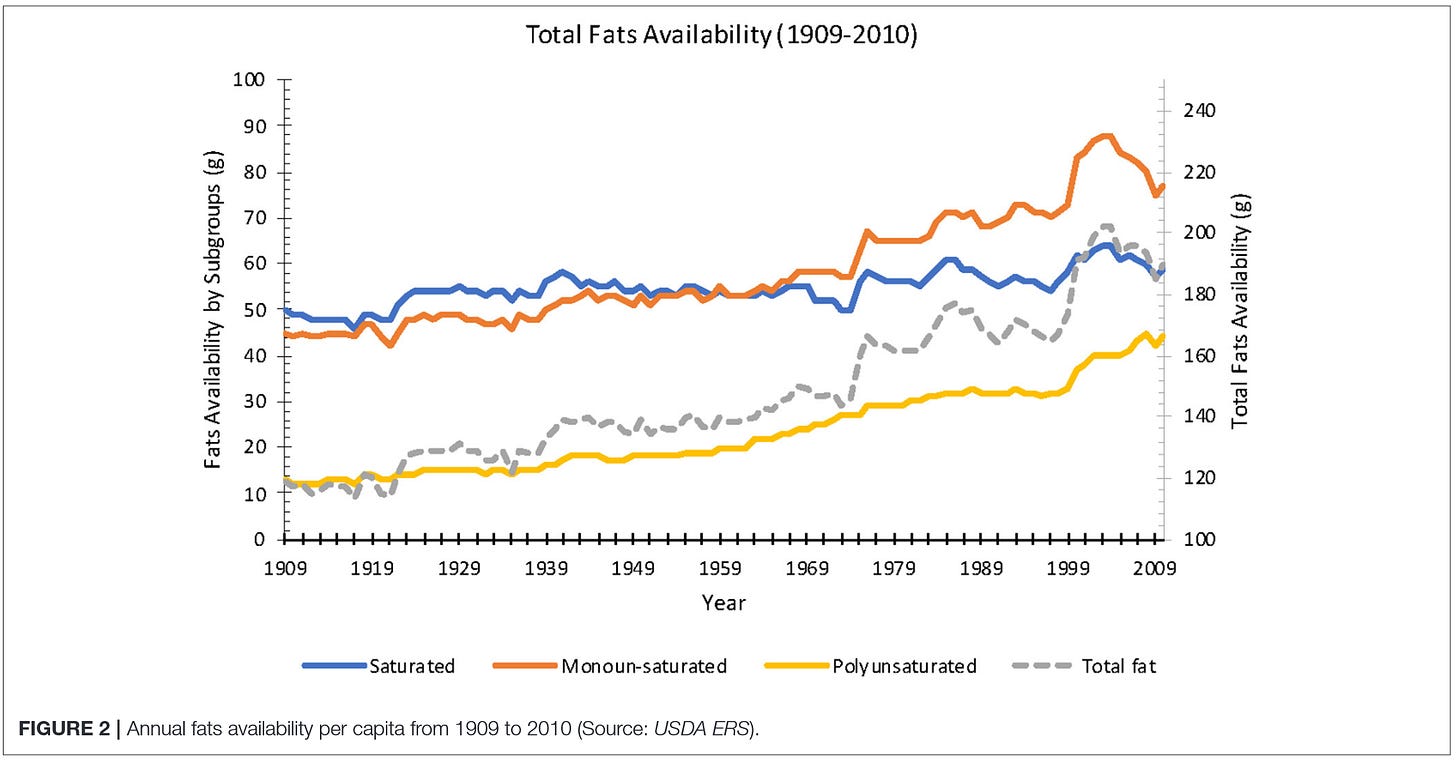

There isn’t a hint of evidence that decreasing the proportion of saturated fat and replacing it with poly- and mono-unsaturated fats will decrease chronic disease: this is what we have been doing for the last 100+ years as we have seen chronic disease skyrocket.

Are my criticisms of their methodology valid? Here’s a commentary on this paper by a famed epidemiologist (hat tip to ZahcM)

“Yet again these studies show that the exposure that is accompanied by large differences in other adverse health exposures – e.g. more than double the rate of cigarette smoking in the highest quartile vs lowest quartile of butter consumption is associated with worse health outcomes. That these differences cannot be taken into account by the statistical models the authors use is well known; measurement error and unmeasured factors ensure this. It is now more than 30 years since these authors published two high profile papers back to back in the New England Journal of Medicine claiming that vitamin E supplement use would reduce heart disease risk by 40%. The claims were incorrect, but many people believed them—the story was the headline news in the New York Times—and started taking vitamin E supplements. However randomised trials later showed this was nonsense: there was no benefit. This is documented in the first few minutes of this recent talk

“As in the conclusion of my blog [(Davey Smith, 2024)] on the same authors’ ‘dark chocolate’ paper, the interesting question this paper raises is ‘why do supposedly legitimate journals keep publishing papers like this?’.” (Davey Smith, 2025)

Davey Smith is pointing out the same flaw, their epidemiology keeps getting refuted by RCTs, which they often ignore in order to keep publishing more papers.

And why does our government fund them? Hopefully that will soon end.

P.S. 2025-03-14

Follow-up to "Butter and Plant-Based Oils Intake and Mortality"

“So I’m not even going to waste our time on going through their detailed analysis. Garbage in still results in garbage out.”

References

Abdelhamid, A. S., Brown, T. J., Brainard, J. S., Biswas, P., Thorpe, G. C., Moore, H. J., Deane, K. H., Summerbell, C. D., Worthington, H. V., Song, F., & Hooper, L. (2020). Omega-3 fatty acids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3(3), CD003177. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003177.pub5

Archer, E., Hand, G. A., & Blair, S. N. (2013). Validity of U.S. Nutritional Surveillance: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Caloric Energy Intake Data, 1971–2010. PLOS ONE, 8(10), e76632. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076632

Bajunaid, R., Niu, C., Hambly, C., Liu, Z., Yamada, Y., Aleman-Mateo, H., Anderson, L. J., Arab, L., Baddou, I., Bandini, L., Bedu-Addo, K., Blaak, E. E., Bouten, C. V. C., Brage, S., Buchowski, M. S., Butte, N. F., Camps, S. G. J. A., Casper, R., Close, G. L., … Speakman, J. R. (2025). Predictive Equation Derived from 6,497 Doubly Labelled Water Measurements Enables the Detection of Erroneous Self-Reported Energy Intake. Nature Food, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01089-5

Christakis, G., Rinzler, S. H., Archer, M., & Kraus, A. (1966). Effect of the Anti-Coronary Club Program on Coronary Heart Disease Risk-Factor Status. JAMA, 198(6), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1966.03110190079022

Crowe, K. (2018, May 5). University of Twitter? Scientists give impromptu lecture critiquing nutrition research [News]. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/second-opinion-alcohol180505-1.4648331

Davey Smith, G. (2024, December 4). And Today’s Random (and Dubious) Medical News Is: Dark Chocolate Prevents Diabetes [Blog]. University of Bristol: IEureka! https://ieureka.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2024/12/04/dark-chocolate-diabetes/

Davey Smith, G. (2025, March 6). Expert Reaction to Study Looking at Butter or Vegetable Oils and Mortality [Blog]. Science Media Centre. https://www.sciencemediacentre.org/expert-reaction-to-study-looking-at-butter-or-vegetable-oils-and-mortality/

Hooper, L., Al‐Khudairy, L., Abdelhamid, A. S., Rees, K., Brainard, J. S., Brown, T. J., Ajabnoor, S. M., O’Brien, A. T., Winstanley, L. E., Donaldson, D. H., Song, F., & Deane, K. H. (2018). Omega‐6 Fats for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011094.pub3

Hooper, L., Martin, N., Jimoh, O. F., Kirk, C., Foster, E., & Abdelhamid, A. S. (2020). Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub2

Lee, J. H., Duster, M., Roberts, T., & Devinsky, O. (2022). United States Dietary Trends Since 1800: Lack of Association Between Saturated Fatty Acid Consumption and Non-communicable Diseases. Frontiers in Nutrition, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.748847

Sacks, F. M., Lichtenstein, A. H., Wu, J. H. Y., Appel, L. J., Creager Mark, M. A., Kris-Etherton, P. M., Miller, M., Rimm, E. B., Rudel, L. L., Robinson, J. G., Stone, N. J., Van Horn, L. V., & on behalf of the American Heart Association. (2017). Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 136(3), e1–e23. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510

Wang, D. D., Li, Y., Chiuve, S. E., Stampfer, M. J., Manson, J. E., Rimm, E. B., Willett, W. C., & Hu, F. B. (2016). Association of Specific Dietary Fats With Total and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(8), 1134–1145. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2417

Zhang, Y., Chadaideh, K. S., Li, Y., Li, Y., Gu, X., Liu, Y., Guasch-Ferré, M., Rimm, E. B., Hu, F. B., Willett, W. C., Stampfer, M. J., & Wang, D. D. (2025). Butter and Plant-Based Oils Intake and Mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2025.0205

And a relentlessly over-credulous AP to breathlessly "report" such garbage

There is a sense in which swapping saturated fatty acids for linoleic acid will consistently improve insulin sensitivity and reduce risk of cancer and heart attack. Norwegian animal scientists came up with the explanation back in 2010. "Because arachidonic acid (AA) competes with EPA and DHA as well as with LA, ALA and oleic acid for incorporation in membrane lipids at the same positions, all these fatty acids are important for controlling the AA concentration in membrane lipids, which in turn determines how much AA can be liberated and become available for prostaglandin biosynthesis following phospholipase activation. Thus, the best strategy for dampening prostanoid overproduction in disease situations would be to reduce the intake of AA, or reduce the intake of AA at the same time as the total intake of competing fatty acids (including oleic acid) is enhanced, rather than enhancing intakes of EPA and DHA only. Enhancement of membrane concentrations of EPA and DHA will not be as efficient as a similar decrease in the AA concentration for avoiding prostanoid overproduction." https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2875212/

Note that at high enough concentrations in the bloodstream, all of the unsaturated fatty acids mentioned above, including linoleic acid, will actually dampen prostanoid overproduction. Saturated fatty acid molecules are not mentioned. That's because they cannot compete with arachidonic acid molecules for membrane lipid positions normally occupied by AA and the other unsaturated fatty acid molecules. That explains this AI Overview that comes up when I do a 'Calder Linoleic Acid 2024' web search. "Recent research in 2024 suggests that linoleic acid (LA), a primary dietary n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, has cardiometabolic benefits rather than the previously feared harmful effects, with higher LA intakes correlating to reduced risks of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes."

Two articles about linoleic acid were pubiished in quick succession in dfferent journals. Kristina H. Jackson, William S. Harris, Martha A. Belury, & Philip C. Calder were co-authors of both articles.

The September article was entitled Beneficial effects of linoleic acid on cardiometabolic health: an update. https://lipidworld.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12944-024-02246-2

The October article was entitled 'Perspective on the health effects of unsaturated fatty acids and commonly consumed plant oils high in unsaturated fat'. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11600290/

Both articles are excellent examples of paltering - using the truth to mislead.

For some reason Philip Calder doesn't seem to realize that their conclusions are based on an incomplete data set. Calder was president of the International Society for the Study of Fatty Acids and Lipids (ISSFAL) from 2009 to 2012. Apparently, he forgot this declaration. "All agreed that a 5-year randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of historically low (2%) with currently high (7.5%) linoleic acid intakes on cardiac endpoints would address the knowledge gap about the effects of different omega-6 PUFA intakes on the risk of heart disease." https://karger.com/anm/article/58/1/59/40551/ISSFAL-2010-Dinner-Debate-Healthy-Fats-for-Healthy

It's likely the study would have shown that 2% or less linoleic acid intake would translate into a huge reduction in mortality no matter how much saturated fat subjects consumed.

As far as I can tell, that sort of study was never funded, so the knowledge gap persists.